Comparing Government Incentives for Electric Vehicles in Different Countries

A Comparison of Policy Measures Promoting Electric Vehicles in 20 Countries

Bakker S, Maat K, van Wee B (2014) Stakeholders interests, expectations, and strategies regarding the development and implementation of electric vehicles: the case of the Netherlands. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 66(1):5264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2014.04.018

Article Google Scholar

Bakker S, Trip JJ (2013) Policy options to support the adoption of electric vehicles in the urban environment. Transp Res Part D Transp Environ 25:1823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2013.07.005

Article Google Scholar

Bakker S, Trip JJ (2015) An analysis of the standardization process of electric vehicle recharging systems. In: Filho WL, Kotter R (eds) E-mobility in Europe: trends and good practice. Springer, Cham, pp 5571

Google Scholar

Baran R, Legey LFL (2013) The introduction of electric vehicles in Brazil: impacts on oil and electricity consumption. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 80(5):907917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.10.024

Article Google Scholar

Beltramello A (2012 Sept) Market development for green cars. OECD Green Growth Pap 3:158. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k95xtcmxltc-en

Benvenutti LMM, Ribeiro AB, Forcellini FA, Maldonado MU (2016) The effectiveness of tax incentive policies in the diffusion of electric and hybrid cars in Brazil. In: 41st Congresso Latinoamericano de Dinamica de Sistemas, So Paulo

Google Scholar

Berman B (2017) Incentives for plug-in hybrids and electric cars. Plugincars. http://www.plugincars.com/federal-and-local-incentives-plug-hybrids-and-electric-cars.html. Accessed 27 Apr 2017

Bundesamt fr Energie (2017) Kantonale Motorfahrzeugsteuern: Rabatte fr energieeffiziente Fahrzeuge. http://www.bfe.admin.ch/energieetikette/00886/02038/index.html?lang=de&dossier_id=02083. Accessed 4 Apr 2017

ChargeHub (2017) Charging stations. https://chargehub.com/en/charging-stations-map.html. Accessed 27 Apr 2017

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

Google Scholar

Domingues JM, Pecorelli-Peres LA (2013) Electric vehicles, energy efficiency, taxes, and public policy in Brazil. Law Bus Rev Am 19(1):5580

Google Scholar

EAFO (2017a) Incentives & legislation. http://www.eafo.eu/incentives-legislation. Accessed 6 Apr 2017

EAFO (2017b) Electric vehicle charging infrastructure. http://www.eafo.eu/electric-vehicle-charging-infrastructure. Accessed 26 Apr 2017

Environmental Protection Department (2017) Promotion of electric vehicles in Hong Kong. http://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/english/environmentinhk/air/prob_solutions/promotion_ev.html Accessed 3 Apr 2017

European Commission (2018) Reducing CO2 emissions from passenger cars. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/transport/vehicles/cars_en. Accessed 1 Feb 2018

EV-Volumes (2017) EV-Volumes. http://www.ev-volumes.com/. Accessed 20 June 2017

Figenbaum E, Assum T, Kolbenstvedt M (2015) Electromobility in Norwayexperiences and opportunities. Res Transp Econ 50:2938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2015.06.004

Article Google Scholar

Gazeta R (2016) Subsidizing purchases of electric cars would make perfect sense. Analytical Center for the Government of the Russian Federation. http://ac.gov.ru/en/commentary/09599.html. Accessed 4 Apr 2017

Government of NCT of Delhi (2016) Budget 20162017. http://delhi.gov.in/wps/wcm/connect/DoIT_Planning/planning/budget+of+delhi/budget+2016-17. Accessed 20 Apr 2017

Haddadian G, Khodayar M, Shahidehpour M (2015) Accelerating the global adoption of electric vehicles: barriers and drivers. Electr J 28(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2015.11.011

Hao H, Ou X, Du J, Wang H, Ouyang M (2014) Chinas electric vehicle subsidy scheme: rationale and impacts. Energy Policy 73:722732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.05.022

Article Google Scholar

Holtsmark B, Skonhoft A (2014) The Norwegian support and subsidy policy of electric cars. Should it be adopted by other countries? Environ Sci Policy 42:160168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.06.006

Article Google Scholar

IEA IA-HEV (2008) Hybrid and electric vehicles: the electric drive gains momentum. http://www.ieahev.org/news/annual-reports/

IEA IA-HEV (2011) Hybrid and electric vehicles: the electric drive plugs in. http://www.ieahev.org/news/annual-reports/

IEA IA-HEV (2012) Hybrid and electric vehicles: the electric drive captures the imagination. http://www.ieahev.org/news/annual-reports/

IEA IA-HEV (2013) Hybrid and electric vehicles: the electric drive gains traction. http://www.ieahev.org/news/annual-reports/

IEA IA-HEV (2014) Annual report 2013: hybrid and electric vehiclesthe electric drive accelerates. http://www.ieahev.org/news/annual-reports/

IEA IA-HEV (2016) Annual report 2015: hybrid and electric vehiclesthe electric drive commutes. http://www.ieahev.org/news/annual-reports/

JAMA (2010a) The motor industry of Japan 2010. http://jama-english.jp/publications/MIJ2010.pdf

JAMA (2010b) Japanese government incentives for the purchase of environmentally friendly vehicles. Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association. http://www.jama.org/japanese-government-incentives-for-the-purchase-of-environmentally-friendly-vehicles/

Kim S, Yang Z (2016) Promoting electric vehicles in Korea. International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). http://www.theicct.org/blogs/staff/promoting-electric-vehicles-in-korea

Li Y (2016) Infrastructure to facilitate usage of electric vehicles and its impact. Transp Res Procedia 14:25372543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2016.05.337

Article Google Scholar

Lieven T (2015) Policy measures to promote electric mobilitya global perspective. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 82:7893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2015.09.008

Article Google Scholar

Marchn E, Viscidi L (2015) The outlook for electric vehicles in Latin America. http://www.thedialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Green-Transportation-The-Outlook-for-Electric-Vehicles-in-Latin-America.pdf

Maurer J (2014) Taiwan setzt bei Elektromobilitt Prioritten. Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI). http://www.gtai.de/GTAI/Navigation/DE/Trade/Maerkte/suche,t=taiwan-setzt-bei-elektromobilitaet-prioritaeten,did=1081172.html. Accessed 5 Apr 2017

Mock P, Yang Z (2014) Driving electrificationa global comparison of fiscal incentive policy for electric vehicles. International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). http://www.theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/ICCT_EV-fiscal-incentives_20140506.pdf

NationMaster (2017) Motorway length by country. http://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Transport/Road/Motorway-length. Accessed 5 May 2017

Netherlands Enterprise Agency (2017) Electric transport in the Netherlands. https://www.rvo.nl/sites/default/files/2017/04/Highlights-2016-Electric-transport-in-the-Netherlands-RVO.nl_.pdf

OECD/IEA (2016) Global EV outlook 2016: beyond one million electric cars. International Energy Agency (IEA). https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/global-ev-outlook-2016.html. Accessed 18 Apr 2017

Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy (2018) Electric vehicles: tax credits and other incentives. https://energy.gov/%0Aeere/electricvehicles/electric-vehicles-tax-credits-and-other-incentives%0A. Accessed 5 Jan 2018

OICA (2017a) Sales of new vehicles 20052016. Organisation Internationale des Constructeurs dAutomobiles (OICA). http://www.oica.net/category/sales-statistics/. Accessed 20 June 2017

OICA (2017b) 2016 Production statistics. Organisation Internationale des Constructeurs dAutomobiles (OICA). http://www.oica.net/category/production-statistics/2016-statistics/. Accessed 15 Nov 2017

PlugShare (2017) EV charging station map. https://www.plugshare.com/. Accessed 26 Apr 2017

Prefeitura de So Paulo (2015) Veculos eltricos e hbridos podero ter desconto de 50% do IPVA. http://capital.sp.gov.br/noticia/veiculos-eletricos-e-hibridos-poderao-ter-desconto. Accessed 20 Apr 2017

PwC (2016) 2016 Global automotive tax guide. https://www.pwc-wissen.de/pwc/de/shop/publikationen/Global+Automotive+Tax+Guide/?card=20976

Rokadiya S, Bandivadekar A (2016) Hybrid and electric vehicles in India: current scenario and market incentives. http://www.theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/India-hybrid-and-EV-incentives_working-paper_ICCT_27122016.pdf

Selya AS, Rose JS, Dierker LC, Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ (2012) A practical guide to calculating Cohens f2, a measure of local effect size, from PROC MIXED. Front Psychol 3:16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00111

Sierzchula W, Bakker S, Maat K, Van Wee B (2014) The influence of financial incentives and other socio-economic factors on electric vehicle adoption. Energy Policy 68:183194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.01.043

Article Google Scholar

Teixeira ACR, da Silva DL, de Neto LVBM, Diniz ASAC, Sodr JR (2015) A review on electric vehicles and their interaction with smart grids: the case of Brazil. Clean Technol Environ Policy 17(4):841857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-014-0865-x

Article Google Scholar

The Norwegian Tax Administration (2017) Pay annual motor vehicle tax. http://www.skatteetaten.no/en/person/cars-and-other-vehicles/annual-motor-vehicle-tax/pay/. Accessed 16 Nov 2017

The World Bank (2017) GDP per capita (current US$). The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD. Accessed 15 November 2017

vant Hull C, Linnenkamp M (2015) Rolling out e-mobility in the MRA-electric region. In: Filho WL, Kotter R (eds) E-mobility in Europe: trends and good practice. Springer, Cham, pp 127140

Google Scholar

van der Steen M, van Schelven RM, Kotter R, van Twist MJW, van Deventer P (2015) EV policy compared: an international comparison of governments policy strategy towards e-mobility. In: Filho WL, Kotter R (eds) E-mobility in Europe: trends and good practice. Springer, Cham, pp 2753

Google Scholar

Worldometers (2017) World population by country. http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/. Accessed 25 Apr 2017

Zhang Y, Yu Y, Zou B (2011) Analyzing public awareness and acceptance of alternative fuel vehicles in China: the case of EV. Energy Policy 39(11):70157024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.07.055

Article Google Scholar

Zhu G, Hein CT, Ding Q (2017) Case studyChinas regulatory impact on electric mobility development and the effects on power generation and the distribution grid. In: Liebl J (ed) Grid integration of electric mobility: 1st international ATZ conference. Springer, Wiesbaden, pp 1329

Google Scholar

These Countries Are Adopting Electric Vehicles the Fastest

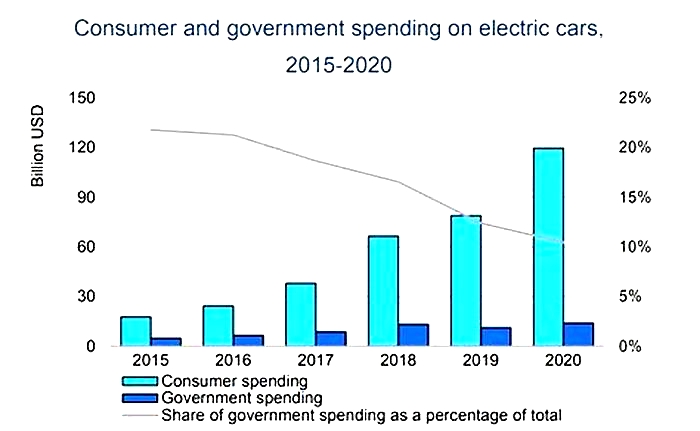

Electric vehicle sales have been growing exponentially due to falling costs, improving technology and government support. Globally, 10% of passenger vehicles sold in 2022 were all-electric, according to analysis ofdata from the International Energy Agency. Thats 10 times more than it was just five years earlier.

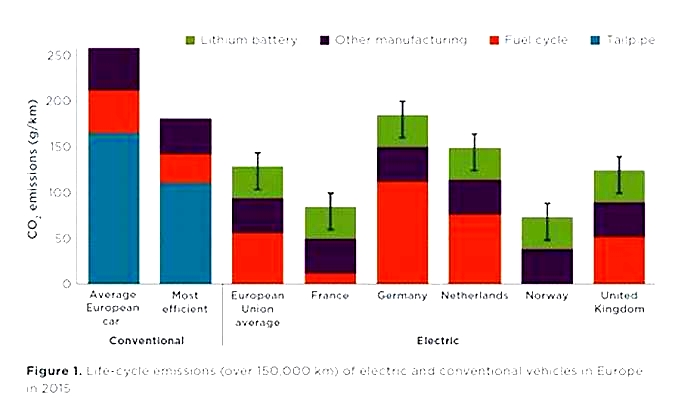

Electric Vehicles (EVs) producefewer greenhouse gas emissionsthan internal combustion engine vehicles, such as gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles. Once the electric grid shifts to zero-carbon power, emissions will be even lower. For this reason,ramping up EVswill be one of the mostimportant stepsin reducing transportation emissions alongsidereducing private vehicle travelandshifting to public transit, biking or walking.

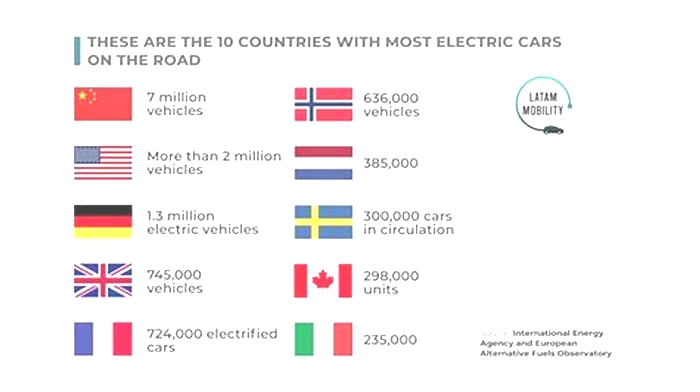

There are already a number of countries switching to EVs at impressive rates. The top 5 countries with the highest share of EV sales are Norway (all-electric vehicles made up 80% of passenger vehicle sales in 2022), Iceland (41%), Sweden (32%), the Netherlands (24%) and China (22%), according to our analysis. Chinas place on this list is especially significant considering it is the biggest car market in the world. The other two biggest car markets have lower EV sales but are growing quickly: the European Union (12%) and the United States (6%).

Globally, EVs need to grow to75% to 95%of passenger vehicle sales by 2030 to be consistent with international climate goals that limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) and prevent many harmful impacts from climate change, according to a high-ambition scenario fromClimate Action Tracker. This target is within reach given recent exponential growth in EV sales. The average annual growth rate was 65% over the past five years; over the next eight years the world needs an average annual growth rate of only 31%.

National EV Sales Follow a Pattern of Exponential Growth

While EV sales have started accelerating at different years for different countries, they are all following a similar S-curve pattern of growth. This is a typical trajectory for the adoption of innovative technologies. Once a technology reaches atipping point for example, when EVs become cheaper than traditional gas- or diesel-powered vehicles the trajectory curves upward. Eventually, growth diminishes as the technology approaches 100% saturation. When it comes to EVs, no countries have reached this slowing-down phase yet, though Norway may be close. The initial acceleration and eventual slowdown create an S-curve. It will never be a perfect S-shape because policy changes and social and economic factors can speed up or slow down rates of adoption, but the overall pattern holds in most cases.

Falling costs and advancing technology have made it possible for EV sales to accelerate faster today than in the past. Our analysis of the International Energy Agencys EV Data Explorer shows that countries where EV sales reached 1% in the past five years have grown at a faster rate than countries that did so earlier.

For example, Indias EV sales grew from 0.4% to 1.5% in just one year from 2021 to 2022. That's about three times faster than the global average, which took three years to grow from 0.4% EV sales in 2015 to 1.6% in 2018. Israel jumped from 0.6% EV sales to 8.2% in just two years, from 2020 to 2022. It took the world more than five years to achieve that much growth, from 0.5% in 2016 to 6.2% in 2021.

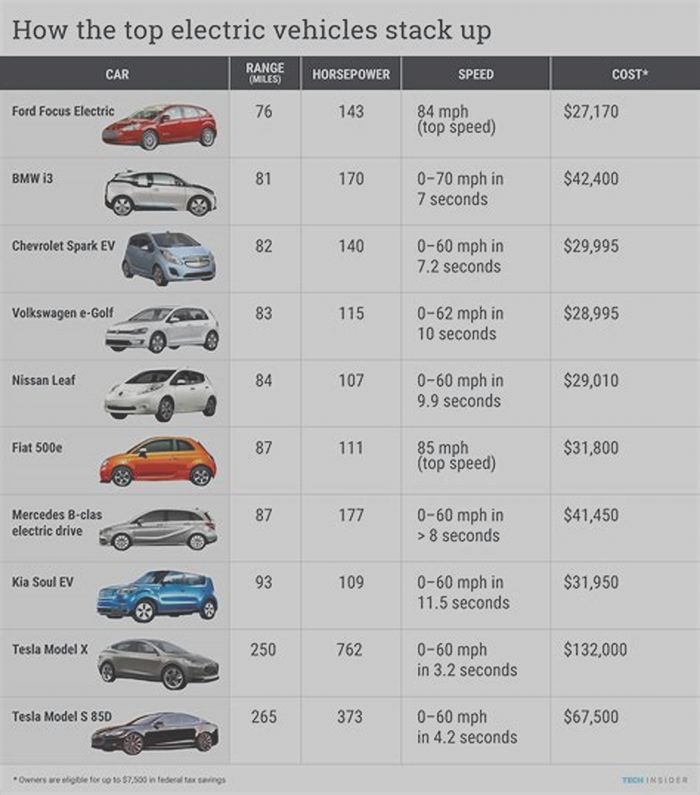

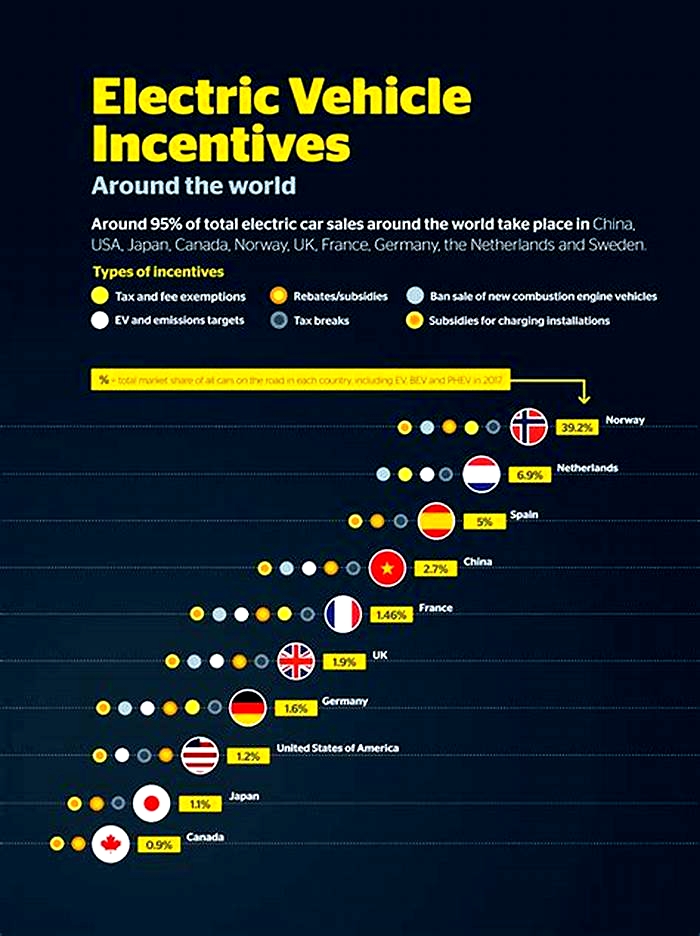

So far most of the EV leaders have been high-income countries, like in Scandinavia, or countries with a lot of market power, like China. Strong government policy and financial incentives from these countries paved the way for a dynamic EV industry to rise and helped costs to fall. Now as the economics of EVs become more favorable, other countries at lower income levels or in different national situations may be able to follow in the same footsteps or go even faster.

How the Largest Car Markets Can Drive Industry Change

Helping the world transition to electric vehicles largely relies on the performance of the three biggest car markets China, Europe and the United States which are collectively responsible for 60% of all global car sales. All three markets have seen big upticks in EV sales in the past few years. Chinas EV sales share is currently double the global average. Europes EV sales share is slightly above the global average. The United States EV sales share is about one year behind the global average (in 2022 the U.S. was at 6.2% EV sales, which is exactly what the world was at in 2021). Sales in the U.S. are poised to grow quickly after theInflation Reduction Actspurred$62 billionin EV investments during its first year.

Sales are still low in India and Japan, the fourth- and fifth-biggest car markets respectively. However, they are finally beginning to accelerate, and as recent sales data has shown, late-adopting countries often grow faster than the early adopters.

2 Countries Achieving Electric Vehicle Success

Lets dive deeper into Norway and China, two of the countries that have been most successful in scaling up EVs, to learn from their experiences.

1) Norway Is the Only Country Where the Majority of Car Sales are All-Electric

Norway is one of thecoldestregions in the world and is crisscrossed by fjords that make some areas difficult to access. Given concerns that EV batteries dont run effectively in low temperatures and dont have as long a range as gasoline vehicles, one would expect that Norway would be one of the last regions to adopt EVs. To the contrary, Norway and its Scandinavian neighbors such as Iceland and Sweden are far and away the leaders in EV adoption. Eight out of 10 passenger car sales in Norway were all-electric vehicles in 2022, with 150,000 sold in total.

Norway is so far ahead of the pack because the government has deliberately and consistently promoted EVs, starting those efforts in 1990, long before the rest of the world. It has a target to phase out internal combustion engine vehicle sales by 2025, the earliest of any country.

There are three reasons why Norways efforts to make EVs the default option for new car buyers have been successful:

First, government incentives have made EVs the best financial choice for consumers. Norwegians who buy all-electric vehicles do not have to pay high value-added taxes or registration taxes and receive other financial benefits as well. This eliminates a substantial portion of the cost of buying and owning an EV. These incentives were gradually rolled out in the 1990s and early 2000s,with supportfrom multiple governments and all political parties. The government was originallytrying to supporta Norwegian EV brand called TH!NK. The company wasnt successful and most Norwegian cars are imported from abroad, but the government continued to promote EVs due to the environmental benefits.

Even with generous incentives, EVs didnt take off until the technology had advanced. The real turning point was around 2012, when the total cost of owning an EV over its lifetime (including the costs of purchasing, maintaining and charging the vehicle) becamecheaperthan the total cost of owning a traditional gas- or diesel-powered vehicle, when including all the tax breaks. By 2021, EVs were also on average 5,000 euroscheaper to purchasewhen including all the tax breaks.

Second, the government hasinvested heavilyin EV chargers and as a result Norway has the most public fast chargers per capita of any country in the world. These can get an EV battery from zero to 80% in as little as 20 minutes. In addition, Norway has established aright to chargefor people living in apartment buildings and providesgrantsfor housing associations to install their own chargers.

Third, Norway has also provided EV owners with some attractive perks, such as free parking in cities, exemptions or reductions in road tolls, access to priority bus lanes and reduced rates for EVs to be transported by ferry (ferries are frequently used given Norways fjord-covered landscape).

Given the success of its EV policies, the government has started graduallyrolling backEV incentives for luxury cars and some of the other perks for all EVs. Now that everyone in Norway is buying EVs, it no longer makes sense to allow all cars to have bus lane access and free parking. Plus, some of these policies may encourage people to choose car travel over public transit, which would increase emissions, so Norway is now more consciouslyconsideringhow to promote other transport options besides private cars.

2) China Sold More EVs Last Year Than the Rest of the World Combined

China is by far the biggest player when it comes to EVs. In 2022, 22% of passenger vehicles sold in China were all-electric, which adds up to 4.4 million sales. Thats higher than the 3 million EVs sold in the rest of the world combined. Chinas support for EVs has helped drive down battery costs and make EV adoption easier all over the world.

China, which was far behind other countries in the production of internal combustion engine vehicles, saw EVs as astrategic investmentin a new area of automobile manufacturing where it could develop an edge if it started early enough. It was also interested in the role EVs could play in reducing air pollution and dependence on imported oil.

In 2009 and 2010, Chinafirst rolled outfinancial subsidies and tax breaks for both EV producers and consumers, starting with pilot cities around the country. Cities could customize the amount and type of EV subsidies to fit their needs and worked with local EV companies to help them grow. For example, Chinese EV company BYDstarted outwith close ties to the city of Shenzhen and has since grown to be one of thebiggest EV producersin the world. After the pilot cities programs, China continued to spend billions of dollars on various national and local subsidies and tax breaks. In 2018, China began a transition to a market-based zero-emissions vehiclecredit system, adapted from Californias zero-emissions vehicle mandate, to replace direct subsidies. The transition has been gradual, and some of the EVsubsidiesandtax breakshave been extended past their planned expiration date.

Overall, the industrial promotion policies have been effective. Today,eight out of the top 10 EV modelssold in China are made by Chinese companies, and China has begun toexportEVs globally. Chinese consumers can choose from nearly300 EV models, more than anywhere else. Chinese companies have also done more than any other country to develop affordable EV models. In many other countries the focus has been on larger vehicles which require more expensive batteries, but in China, smaller vehicles are the norm. BYD recentlylaunchedan $11,000 EV hatchback, and the $4,500 Wuling Hongguang Mini EV has been one of the top sellers.

The retail price of many electric cars in China hasfallen belowthat of comparable gas or diesel-powered vehicles, when including subsidies. And Teslas entry into the Chinese market has spurred aprice warthat is pushing down EV costsfurther.

Another major factor that has encouraged uptake is that China has installed 760,000 public fast charging points and 1 million public slow charging points, which is more than the rest of the world combined. And like Norway, China has extended non-monetary benefits to EV drivers, mostly at the city level. For example, in the city of Beijing, car license plates are rationed and have a long wait time, but the process is essentiallywaivedfor EV buyers.

Government Leadership Is Key for Faster EV Uptake

The experiences from Norway and China can provide lessons for other countries. Both countries had governments that made a deliberate choice to promote EVs, invested in public chargers and implemented policies to make EVs cost competitive. EV adoption grew rapidly once EVs were a better financial decision for prospective car buyers than traditional gas- or diesel-powered vehicles, especially when buyers were confident in the range of the vehicles and their ability to easily access public chargers.

Thanks to the policy pushes in countries like Norway and China, it wont take long for cost competitiveness to arrive for more countries, given the falling EV prices, but those governments should not sit back and wait for this to happen given the urgency of the climate crisis. Not every country is as wealthy as Norway or has the market power and government structure of China, but electric vehicles can be an economic and environmental win for awide variety of developing countries.

So far, cost competitiveness has mostly been achieved through subsidies, but these can be quite expensive for government budgets and there are other options too. Policies mandating 100% EV sales are thesingle most effective policyto drive the transition. Currently,16 countries, including Canada, Japan and the United Kingdom, have some form of policy mandating 100% EV sales in 2035 or earlier. More countries should create and enforce such policies. If the EU, U.S. and China all aligned their national regulation to aim for 100% EV sales by 2035, the scaling up of production would lower costs worldwide,bringing forwardcost parity in other countries, such as India, by as much as three years. In addition, countries should increase thenumber of public chargers, and particularly the number of fast public chargers, in order to make EV ownership an easy choice.

The shift to EVs must be done equitably. Governments should incentivize carmakers to produce more affordable EV models. When subsidies are used, they should be targeted at low-income households, which in addition to being equitable is alsomore effectiveat increasing EV adoption, given that low-income households are more sensitive to price changes.

Rapidly increasing EV adoption to reach 75% to 95% of global passenger vehicle sales by 2030 will be challenging, but it is achievable if the world heeds these lessons and keeps up the current rapid pace of change.

Finally, its important to note that increasing EV sales is only part of the story. To decarbonize road transportation, old gas- and diesel-powered vehicles will need to be retired rather than be sold to other drivers or to developing countries and the increasing popularity of large vehicles like SUVs will have to be reversed. Whats more, the goal shouldnt be for everyone to own a car.Transforming the transport systemto increase access to other forms of mobility can lower emissions, reduce automobile-related deaths, save time lost in traffic and limit ecosystem damages.

Data for all-electric vehicle sales in this article is from the International Energy Agency's Global EV Data Explorer, as of September 2023. Data is presented for both all-electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid; author split out the all-electric vehicles.

This article is the second in a series ofdeep-dive analysesfromSystems Change Labexamining countries that are leaders in transformational change. Systems Change Lab is a collaborative initiative which includes an open-sourced data platform designed to spur action at the pace and scale needed to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, halt biodiversity loss and build a just and equitable economy.