Exploring EV Charging Infrastructure Urban vs Rural Challenges

Beyond Cities: Breaking Through Barriers to Rural Electric Vehicle Adoption

July 2022 Update: In November 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (P.L. 117-58), referred to in this article as the bipartisan infrastructure bill, became law, authorizing $7.5 billion in funding for the buildout of 500,000 electric vehicle (EV) chargers. Of that funding, $5 billion will be allocated to states, while the rest will be distributed as grants by the Federal Highway Association with a focus on rural, disadvantaged, and hard-to-reach communities. The Joint Office of Energy and Transportation was created through the Act to facilitate collaborations between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) to deploy electric vehicle chargers. In June 2022, the DOT released a notice of proposed rulemaking that proposed specific standards and requirements for EV charging infrastructure. For more on building out electric vehicle charging infrastructure, check out EESIs briefing. |

- Rural areas have low rates of electric vehicle (EV) adoption, in part because rural areas lack EV charging infrastructure.

- The proposed bipartisan infrastructure bill allocates $7.5 billion for EV charging stations, with priority funding for rural areas. It would be the country's first federal investment in EV charging stations.

- Rescinding bans on direct-to-consumer automotive sales, which currently exist in 17 states, is another important step towards increasing the availability of EVs.

Light-duty, fully-electric vehicle (EV) sales more than doubled during the first half of 2021, outpacing the automotive market's overall 29 percent sales growth, and EVs are expected to account for 2.9 percent of total sales of light-duty vehicles in 2021. However, while these figures show that the push to electrify the automotive sector is well underway in urban and suburban areas, the same cannot be said for rural America. The need to electrify the transportation sector to reduce carbon emissions is clear, but this goal cannot be reached without the inclusion of rural areas, which are home to more than 57 million Americans.

The State of Rural EV Ownership

When compared to metropolitan areas, rural communities and regions have extremely low EV adoption rates, with the vast majority of non-urbanized areas having new electric vehicle registration rates of between zero and half a percent. This equates to fewer than five and, in many cases, zero registered EVs per 10,000 people in the majority of non-metro counties, whereas EV registration in metro counties ranges from 10 to more than 100 registered EVs per 10,000 people. This disparity is also visible at the state level, as states with higher rural populations have significantly lower rates of EV registration.

The Lack of Charging Infrastructure in Rural America

The lack of EV charging infrastructure in rural areas is one of the most significant barriers to rural EV adoption in the United States. While rural areas are home to less than one-fourth of the U.S. population, they cover 97 percent of the country's total land area. Nevertheless, the vast majority of charging infrastructure is concentrated in major cities. Major metro areas have 500 to over 1,000 public outlets per 25 square miles, while most suburban areas have one to 25 outlets and the majority of rural areas and small towns have none. The urban-rural charger divide can also be seen at the state level, as the same rural states with low EV registration rates also have low numbers of EV chargers per mile of road.

The Department of Energys most recent report on EV infrastructure determined that for an EV driver to be no more than three linear miles from a fast-charging station in any city or town, there would need to be a charger density of 56 stations per 1,000 square miles. While the top ten EV metropolitan markets meet this standard, with an average of 65 fast-charging stations per 1,000 square miles, the national average is only 18 stations per square mile. This number is nowhere near dense enough to compete with gas stations, which have an average density of about 960 stations per 1,000 square miles. While this target is for urban areas rather than rural, there are still not enough charging stations in rural areas to match the density of gas stations.

To increase rural EV adoption, states must increase the density of EV charging outlets in rural areas. Increasing the number of available chargers will decrease range anxiety for rural EV adopters. A positive feedback loop is also likely to play a large role in the dynamics of EV ownership and charging availability, with rural rates of EV ownership increasing as more chargers are built in rural areas, and vice versa.

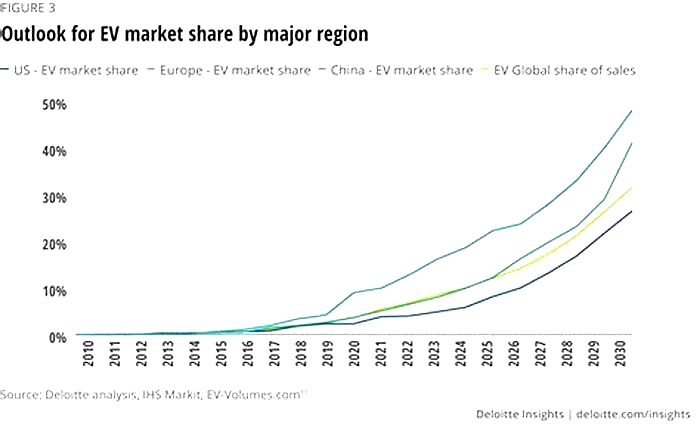

One way to increase charger density is through federal investment in charging infrastructure. While the Biden-Harris Administration initially proposed a $15 billion investment to expand our charging network of 100,000 stations to 500,000 stations, the proposed bipartisan infrastructure bill instead allocates $7.5 billion for EV charging stations, with priority funding for rural areas. It would be the country's first federal investment in EV charging stationsa necessary step to reaching the administrations goal of 50 percent EV market share by 2030.

Electric cooperatives can also play an increasingly influential role in rural EV adoption by bringing charging stations and EV outreach programs to their service areas, which are overwhelmingly rural and make up 56 percent of U.S. land area. White River Electric Association, a member of the Colorado-based Tri-State Generation & Transmission Association, helped install two EV charging stations in the rural mountain community of Meeker, Colorado, where they were well received by locals. Installing chargers in rural downtown areas helps turn small towns into destinations for EV drivers, spurring new economic development, reducing range anxiety, and encouraging EV adoption among residents.

Tri-State has also developed an EV loaner program, in which several EVs purchased by the association can be distributed to co-ops for Ride and Drive events. At these events, utility employees and residential customers alike can experience electric vehicles in person. In Nebraska, for instance, Northwest Rural Public Power Districts Ride and Drive events of August 2020 yielded overwhelmingly positive reactions from customers and dispelled many hesitations about EVs.

Protectionist Dealer Laws

The direct-to-consumer automotive sales bans that exist in many states are another major obstacle to rural EV adoption. These laws prohibit manufacturers from selling cars directly to consumers without the use of dealerships. This means automakers that do not use the dealership model, like Tesla, are banned from selling their cars in states where these laws have been enacted. The bans would also apply to EV startups like Rivian, Lordstown Motors, and Lucid Motors when they start selling vehicles, which is why these companies are fighting to pass laws overturning the bans. New EV carmakers generally dont have the resources necessary to establish nationwide dealership networks.

While supporters of the ban argue that the policy is beneficial because it promotes competition between dealers and drives down prices, opponents argue that there is no reason why dealerships and direct sales models cannot coexist. While direct sales are allowed in 22 states, they are still completely banned in 17 states, many of which have large rural populations. As of 2021, 11 states that prohibit direct sales, including North Dakota, have passed legislation making exceptions for Tesla. To maximize market penetration and allow for higher rates of EV adoption, 28 states must pass direct sale ban exceptions for all EV manufacturers or repeal their bans entirely.

Limited Model Availability

While manufacturers are offering more EV body styles than ever before, model availability remains a significant barrier to EV adoption in rural areas due to the lack of truck options. Pickup trucks remain a functional and cultural staple of rural America. Trucks make up about 20.1 percent of the new car market nationally but are overwhelmingly popular in more rural states like North Dakota and Wyoming, where truck market share surpasses 41 percent. While a good number of sedan and crossover EV options exist, the automotive market has yet to see the release of an all-electric pickup truck. This will soon change once Fords all-electric F-150 Lightning goes on sale in the spring of 2022. With an average of just under 900,000 sales annually over the last three years, the gasoline Ford F-150 is the most popular vehicle in more than 30 states, including North Dakota, Wyoming, and Vermont. If the electric version of the truck proves to be anywhere near as popular as the gas version, the F-150 Lightning could serve as a catalyst for rural America to rapidly adopt electric vehicles. To increase the rate of rural EV ownership, more automakers must begin to produce EVs suited to the needs and lifestyles of rural customers.

.png) |

Moving Forward

While widespread EV adoption in the United States presents many challenges for the nation as a whole, rural areas face additional barriers that prevent EVs from reaching their full potential. Although progress has been made, much more work remains to be done in the areas of charging infrastructure, EV model availability, and state and local policies in order to encourage EV adoption in rural America. While it is clearer than ever that the future of rural transportation is electric, reaching this future will require continued actions by parties of all sizes, from the rural electric co-ops of small towns to automotive manufacturers and the federal government. By implementing EV-friendly infrastructure and policies in rural America, the United States as a whole can more quickly make the transition to clean transportation while ensuring that those living beyond metropolitan areas are not left behind.

Author: Jaxon Tolbert

Authors Note: Special thanks to Jon Jantz of Collaborative Efficiency who helped inform this article.

Shaping the future of fast-charging EV infrastructure

In the past decade, electric vehicles (EVs) have gone from a rare sight on even the busiest road to an increasingly common, affordable option. In 2020, EV sales set new records that surpassed expectations, particularly in countries with an eager customer base and government policies supporting the transition to EVs. Much of this leadership has come from Europe, where EV adoption has surged; by July 2021, for example, two-thirds of Oslos residents owned an EV. According to McKinsey analysis, 45 percent of customers are considering buying an EV.

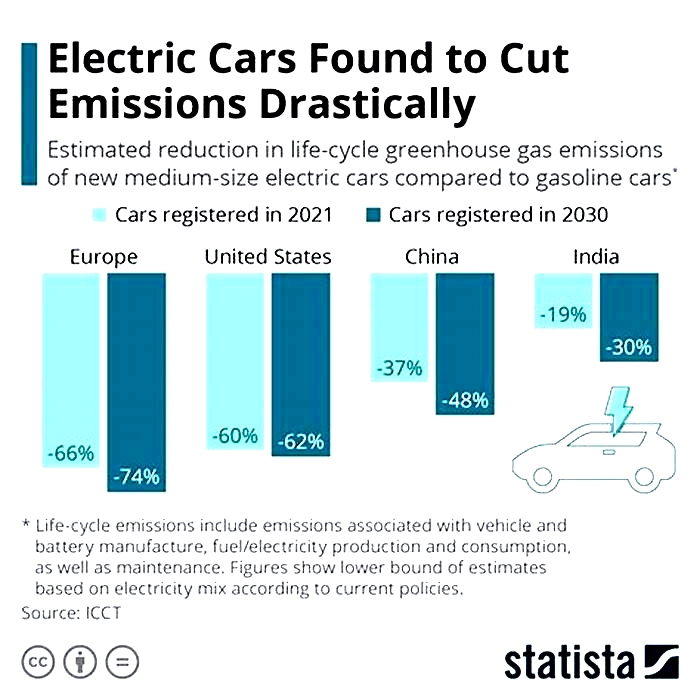

In addition to consumer enthusiasm and government regulations and incentives, the number of industry players committed to phasing out internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles continues to grow. Such commitments are still in early stages, but by 2050 the bans OEMs have announced to date will account for more than half of todays passenger vehicle sales, and the EU is aiming for an ICE ban by 2035, likely pulling other countries commitments forward as well. All signs point to continued growth in the EV market, with Europe leading the charge: McKinsey projections suggest EVs will make up 75 percent of European new car sales by 2030.

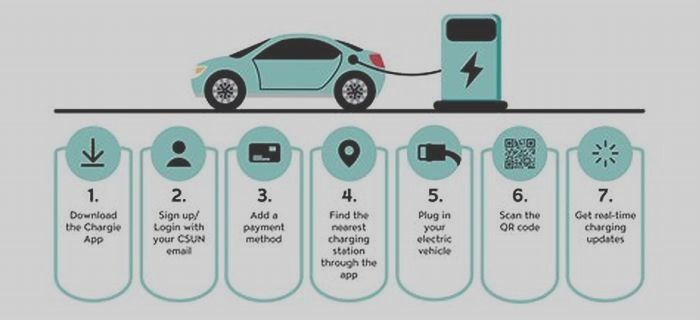

All this growth means we need more places to charge EVsnow. Everywhere from homes and workplaces to retail sites, fleet depots, and on-the-go charging sites, the race is on to build enough public fast-charging stations to meet demand, remove perceived inconvenience for those still hesitating to transition to EVs, and ultimately help meet CO2 emission reduction targets. Some actions governments and companies can take include offering incentives to build private chargers, subsidizing public charging, and investing in production capacity and a skilled workforce.

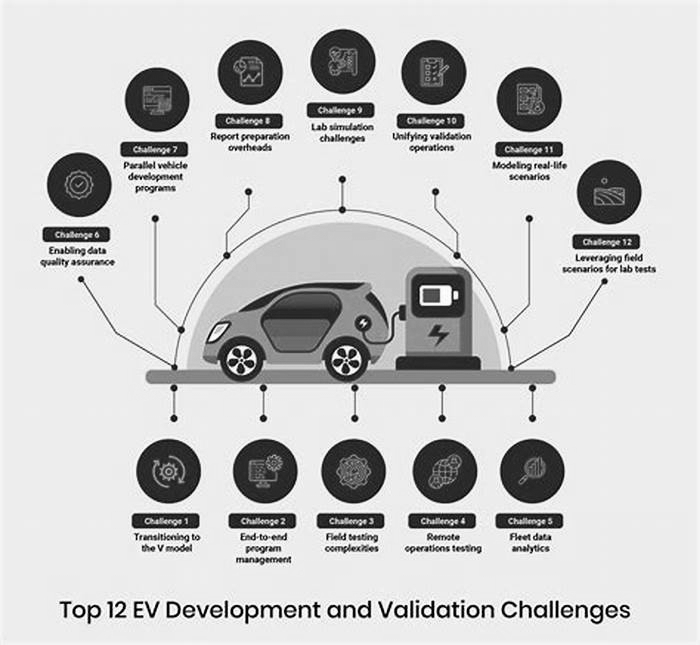

EV charging infrastructure could become a bottleneck for growth

As EVs have become increasingly affordable, one of the primary barriers for consumers is no longer cost but charging convenience. In McKinseys 2020 ACES Consumer Survey, potential EV drivers put the lack of charging infrastructure at the top of the list of barriers to expanded EV adoption. Today, most EV charging is done at home, but the availability and convenience of publicly accessible chargers will be crucial for complete electrification of the vehicle fleet.

Although momentum in charging infrastructure has increasedEuropes public charger count increased fourfold between 2015 and 2020four risks could turn charging into a bottleneck:

- Regulations. In many geographies, securing permits to build chargers, construct sites, and connect to the electric grid can require months, or even years, of planning.

- Grid. Especially in areas with high charging demand, the electrical grid needs to be upgraded to expand power capacitywhich include expensive and time-consuming updates.

- Resources. Several resources are in short supply, including skilled technicians, production capacity for fast-charging hardware, and enough green energy to make EVs fully environmentally friendly.

- Cost. EV charging infrastructure is not cheap; in the European Union, a typical 350-kilowatt (kW) charger can cost $150,000, including hardware, installation, and planning.

Actions to mitigate the threat of EV charging infrastructure shortages

Solution providers and owners and operators of charging networks play a key role in scaling EV-charging infrastructure, yet the broader ecosystem can help address a number of challenges. This includes, among others, OEMs, real estate providers, utilities and grid operators, and infrastructure funds.

With this in mind, governments and companies can take several actions to address the leading risks facing EV charging infrastructure.

Governments

Offer more incentives and mandates for building private chargers. Many countries are finding success with establishing incentive schemes for consumers, such as refunds for installing a wall box. They are also increasingly introducing requirements and subsidies for apartment buildings and other multiunit dwellings to offer chargers, as well as for companies to install chargers at workplacesindeed, chargers will eventually become a standard part of building design. These inducements should be structured to direct money toward the biggest bottlenecks for EV growth in a given communityfor example, earmarking more incentive funding for apartment buildings in dense areas with limited parking.

Subsidize public charging in necessary locations. Subsidiesfor capital expenditure on chargers, installation, and power distribution, as well as ongoing costs for operationcan help draw EV charging to areas where it is most needed. Such subsidies can make it economically viable to build chargers in areas where long-term profitability can outweigh short-term costs. Some governments, such as New York Citys, are funding installation costs to build chargers in high-demand areas; others, such as Germanys, are sponsoring an entire network to be operated by private companies. A successful effort will require modeling of demand, grid capacity, and other factors to determine priorities for investment.

Work with utilities to build out the electric grid. Electric grids will need to expand capacity to ensure they can cover the demand that will be created by a future of EV-covered roads. Governments might direct funding to grid operators earmarked to build capacity starting in areas with high local charging demand. They can also consider developing a new grid fee system that accounts for peak demand charging need, protects the grid from overutilization, and keeps charging economically viable at ultrafast charging locations.

Link incentives and subsidies to use of green energy. Achieving net-zero road emissions requires ensuring EV chargers are distributing 100 percent green energy. Where possible, governments can advance multiple sustainability agendas by requiring recipients of incentives and subsidies to commit to using green energy.

Simplify and standardize permitting. In extreme scenarios, securing a permit for a charger site, including installation and grid updates, can take two years. Streamlining permitting to accelerate throughput will take concerted action at a number of levels of government and in most geographies.

EV charging companies

Invest in production capacity and a skilled workforce. Now is the time for EV charging companies to scale, build out factories and supply chains in relevant regions to match demand, and develop a growth-minded talent strategy. These resources will form the foundation for successful rollouts of chargers in the coming years.

Partner to finance public chargers. Infrastructure funds and other potential investment partners offer alternative funding sources to help build, install, and operate public chargers. Beyond raising money, such partners may also be interested in other methods of funding capital, such as purchasing charging infrastructure assets in exchange for stable returns.

Use data and analytics for network planning. Sophisticated, data-driven planning will be required to identify the best sites for a successful, in-demand charging network. For example, geospatial analytics allow planners to optimize locations based on traffic flows, local grid status, and other relevant factors.

Reduce range anxiety of potential EV drivers. Perception of potential issues with switching from ICE to EV needs to be proactively addressed. Ongoing consumer education efforts around helpful tools (such as integrated trip planning or charger reservations) and additional advantages of EVs (such as integration with a home solar system) is required.

In 2020, the EV rubber hit the road. Over the next decade, EVs will help redefine the intersection of mobility and infrastructureand, in doing so, will, contribute significantly to achieving net-zero emissions targets.