How far will electric cars go in the future

How electric cars are charged and how far they go: your questions answered

How electric cars are charged and how far they go: your questions answered

By Justin Rowlatt

Chief environment correspondent

The announcement that the UK is to ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2030, a full decade earlier than planned, has prompted hundreds of questions from anxious drivers. Im going to try to answer some of the main ones weve had sent in to the BBC.

How do you charge an electric car at home?

The obvious answer is that you plug it into the mains but, unfortunately, it isnt always that simple.

If you have a driveway and can park your car beside your house, then you can just plug it straight into your domestic mains electricity supply.

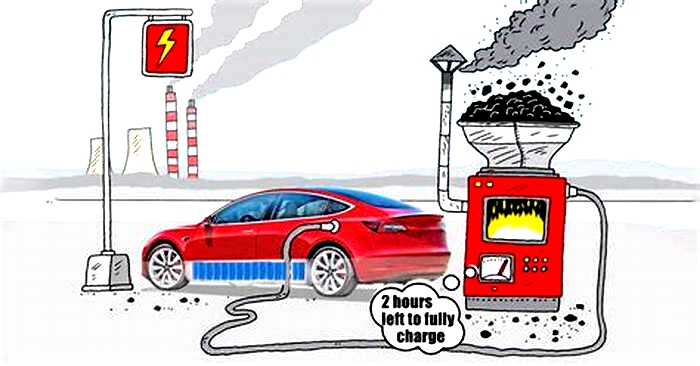

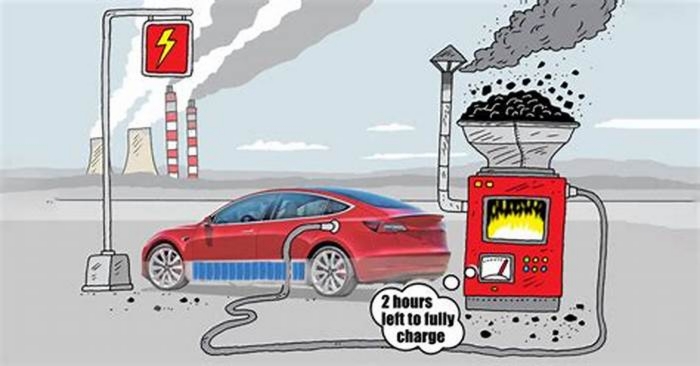

The problem is this is slow. It will take many hours to fully charge an empty battery, depending of course on how big the battery is. Expect it to take a minimum of eight to 14 hours, but if youve got a big car you could be waiting more than 24 hours.

A faster option is to get a home fast-charging point installed. The government will pay up to 75% of the cost of installation (to a maximum of 500), though installation often costs around 1,000.

A fast charger should typically take between four and 12 hours to fully charge a battery, again depending how big it is.

How much will it cost to charge my car at home?

This is where electric vehicles really show cost advantages over petrol and diesel. It is significantly cheaper to charge an electric car than fill up a fuel tank.

The cost will depend on what car youve got. Those with small batteries and therefore short ranges will be much cheaper than those with big batteries that can travel for hundreds of kilometres without recharging.

How much it will cost will also depend on what electricity tariff you are on. Most manufacturers recommend you switch to an Economy 7 tariff, which means you pay much less for electricity during the night when most of us would want to charge our cars.

The consumer organisation Which estimates the average driver will use between 450 and 750 a year of additional electricity charging an electric car.

Will the UK be ready for a 2030 ban on sales of petrol and diesel cars?

What if you dont have a drive?

If you can find a parking space on the street outside your home you can run a cable out to it but you should make sure you cover the wires so people dont trip over them.

Once again, you have the choice of using the mains or installing a home fast-charging point.

What about public charging points?

Many local authorities are putting in street charging points. Look out for lamp posts with a blue light on them. These will have plugs where you can get power.

Lots of new electric cars now have apps installed that will direct you to the nearest charging point. If not, there are a host of websites and downloadable apps that will do the job.

There are already more than 30,000 charging stations in the UK, according to the electricity company EDF. This means there are already more public places to charge than petrol stations. Around 10,000 new charge points were added just in 2019.

And you should expect that number to increase rapidly. Today, the government announced a 1.3bn investment in electric vehicle infrastructure, including charging points across the country.

Public charging points are pretty easy to use, but there are a number of different operators and you often have to be a member to use them.

Some charge a flat fee each month for access; some offer pay-as-you-go charging.

Typically, youll need to use a swipecard or your mobile phone to unlock the charging point. This will allow you to connect the charging cable from your car to the charging point.

A few manufacturers, most notably Tesla, offer access to superchargers. These allow very rapid charging indeed, you might get an 80% charge in just 30 minutes about the time it takes to go to the loo and buy and drink a cup of coffee.

These used to be free to Tesla owners, but now most have to pay to use the Supercharger network.

New charging points are going in all the time

How far can an electric car go?

As you might expect, this depends on which car you choose. The rule of thumb is the more you spend, the further youll go.

The range you get depends on how you drive your car. If you drive fast, youll get far fewer kilometres than listed below. Careful drivers should be able to squeeze even more kilometres out of their vehicles.

These are some approximate ranges for different electric cars.

- Renault Zoe - 394km (245 miles)

- Hyundai IONIQ - 310km (193 miles)

- Nissan Leaf e+ - 384km (239 miles)

- Kia e Niro - 453km (281 miles)

- BMW i3 120Ah - 293km (182 miles)

- Tesla Model 3 SR+ - 409km (254 miles)

- Tesla Model 3 LR - 560km (348 miles)

- Jaguar I-Pace - 470km (292 miles)

- Honda e - 201km (125 miles)

- Vauxhall Corsa e- 336km (209 miles)

It is worth noting that electric vehicle range is expected to steadily increase as battery technology improves.

How long does the battery last?

Once again, this depends on how you look after it.

Most electric car batteries are lithium-based, just like the battery in your mobile phone. Like your phone battery, the one in your car will degrade over time. What that means is it wont hold the charge for so long and the range will reduce.

If you overcharge the battery or try to charge it at the wrong voltage it will degrade more quickly.

Check out whether the manufacturer offers a warranty on the battery many do. They typically last eight to 10 years.

It's worth understanding how they work, because you won't be able to buy a new petrol or diesel car after 2030.

Electric cars: Five big questions answered

Electric cars: Five big questions answered

Elon Musk's Tesla has been one of the front runners in the EV sales race but other manufacturers are gaining

In less than eight years, the government plans to ban the sale of all new petrol and diesel cars and vans and as part of this shift is promising to expand the network of public charging points to 300,000.

It's part of a government strategy in order to help the UK meet its 2050 net zero target, where electric vehicles (EVs ) will soon become the most common option for anyone wanting to buy a brand new car.

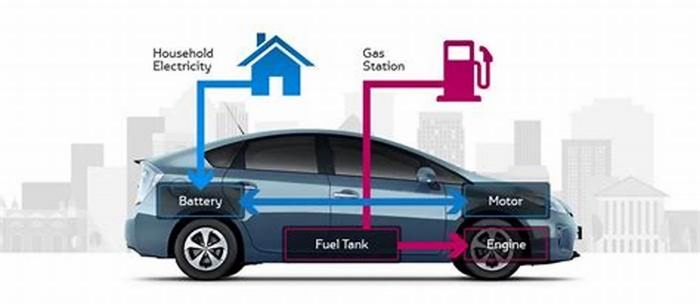

Among the 35 million cars driving around on UK roads just 1.3% were EVs in 2020 but that figure is starting to climb. Battery electric and hybrid cars accounted for nearly a third of new cars leaving dealerships last month, according to The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders. (SMMT).

But would-be buyers still have a lot of reservations.

BBC Radio 5's The Big Green Money Show asked listeners to send in their questions, here are their top five:

Why are electric cars so expensive?

Electric cars usually cost thousands of pounds more than their petrol, or diesel, counterparts. This is because EV batteries are expensive to make and a high level of investment is needed to transform existing factory production lines to manufacture the new technology.

However, costs are expected to come down in the near future: The SMMT forecasts electric and internal combustion engine cars should cost roughly the same "by the end of this decade."

Meanwhile, experts say you should also consider the total spend over the car's lifetime.

The cost of the electricity used to power your EV has been rising sharply recently and will vary according to your household tariff, but it is still cheaper than petrol or diesel fuel per mile.

Melanie Shufflebotham is the co-founder of Zap Map, which maps the UK's charging points. She says if an EV is charged at home "the average price people are paying is roughly 5p per mile". This compares she says, to a cost of between 15-25 pence per mile for petrol or diesel cars.

There are other potential savings too. Vehicle tax is based on how much pollution a car emits, so zero emissions vehicles like electric cars are exempt. Meanwhile, says Melanie Shufflebotham, an EV is usually cheaper to maintain because "typically, a petrol or diesel car has hundreds of moving parts, whereas an electric car doesn't."

For instance, an electric vehicle will not require its oil changing and because it has fewer moving parts, is likely to suffer less wear and tear. The cost of replacing batteries is high, but many manufacturers offer a guarantee of at least eight years.

The UK will need to rapidly expand the existing network of 30,000 public charging points

Are there enough public chargers for all the EV drivers who will need them?

Right now, the UK has around 30,000 public charging points, of which two thirds are "fast" or "rapid" chargers, according to Zap Map. The government announced on Friday plans to expand this ten-fold to 300,000 by 2030.

Last July, the Competition and Markets Authority raised concerns that the on-street charging rollout has been "slow and patchy" and called on the government to set up a national strategy to improve the infrastructure before the 2030 deadline.

The current number of public chargers is "nowhere near enough" says Paul Wilcox, the UK managing director of Vauxhall.

But he believes the situation will improve vastly by 2030 as EVs become more common, because as demand rises, the number of chargers installed will increase. "I'm absolutely confident because once you get the volume of cars you'll get the commercialisation of charging."

Only rapid and ultra-rapid chargers are suitable for drivers wishing to recharge on long journeys. According to Zap Map, at the moment around 5,500 of those exist. Of those - just over 800 are Tesla Superchargers which can only be used by Tesla drivers.

Charging an EV at home - but many people do not have suitable space where they live to do this

What about 'range anxiety' - how far can a fully-charged EV travel?

The distance a car can be driven on a single battery charge is known as range and varies between models.

Peter Rolton, Executive Chairman at Britishvolt, which is building an EV battery factory in Northumberland, says the technology to increase range is improving.

"A hatchback [car] currently has around 200-250 miles range." By the end of the decade, he says better batteries will push that distance by many miles.

EVs are powered by lithium-ion batteries and research is ongoing to improve their range. The game-changer will be if, and when, manufacturers can commercialise the next stage of the technology - known as solid state batteries. These batteries will be lighter and charge much faster than their lithium-ion counterparts.

James Gaade, head of programme management at the Faraday Institution says "many automakers are targeting the introduction of solid-state batteries" within the next decade. These, he says "could herald a step change in EV range."

In a nutshell, these cars are expected to be able to travel much further on a single charge in the future.

What if I am not able to charge at home?

The majority of households in the UK, some 18 million (65%), either have, or could offer, off-street parking for at least one vehicle. according to data from the RAC. However, According to the Competition and Markets Authority that leaves more than eight million households without access to home charging, including some people living in flats.

There are other alternatives, says Melanie Shufflebotham of Zap Map. "Local authorities are beginning to install on-street chargersand then apart from that it's about finding a charger at a local supermarket, or a local charging hub, so you can charge up periodically, as you would with a petrol or diesel car."

However, people relying on public chargers face higher costs to power up their EV than those able to charge at home, with prices varying depending on which company owns the charging point. Public charge points also attract a higher rate of VAT; 20% compared with the 5% paid by domestic users charging at home.

Will we all own cars in the future?

Maybe not. Paul Wilcox of Vauxhall says "seismic changes are coming". He expects to see "a huge rise in things like subscription models", where customers pay monthly to use a car with other costs like insurance and maintenance included.

Another area expected to grow is what's known as 'fractional ownership', or car sharing clubs. Melanie Shufflebotham says car sharing could grow in popularity, until driverless cars eventually become a reality.

"Imagine, just as you'd call up an Uber now, you will have an app to call up an autonomous car to take you where you want to go. In the nearer term I think car sharing is a really important solution."

Download and subscribe to The Big Green Money Show with Deborah Meaden on BBC Sounds, or listen to a shorter version on BBC Radio 5 Live on Fridays.