What happens to electric car batteries after 10 years

Millions of electric car batteries will retire in the next decade. What happens to them?

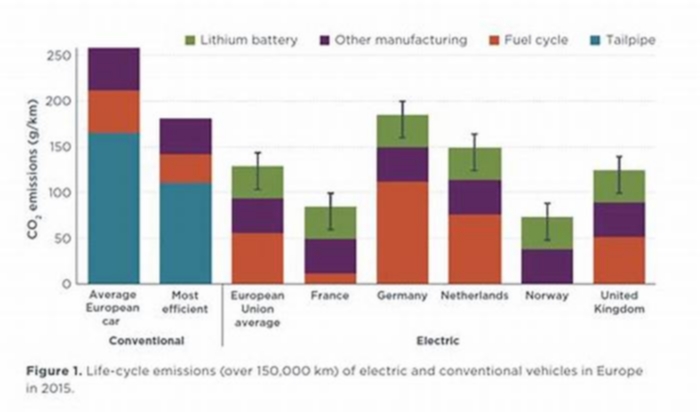

A tsunami of electric vehicles is expected in rich countries, as car companies and governments pledge to ramp up their numbers there are predicted be 145m on the roads by 2030. But while electric vehicles can play an important role in reducing emissions, they also contain a potential environmental timebomb: their batteries.

By one estimate, more than 12m tons of lithium-ion batteries are expected to retire between now and 2030.

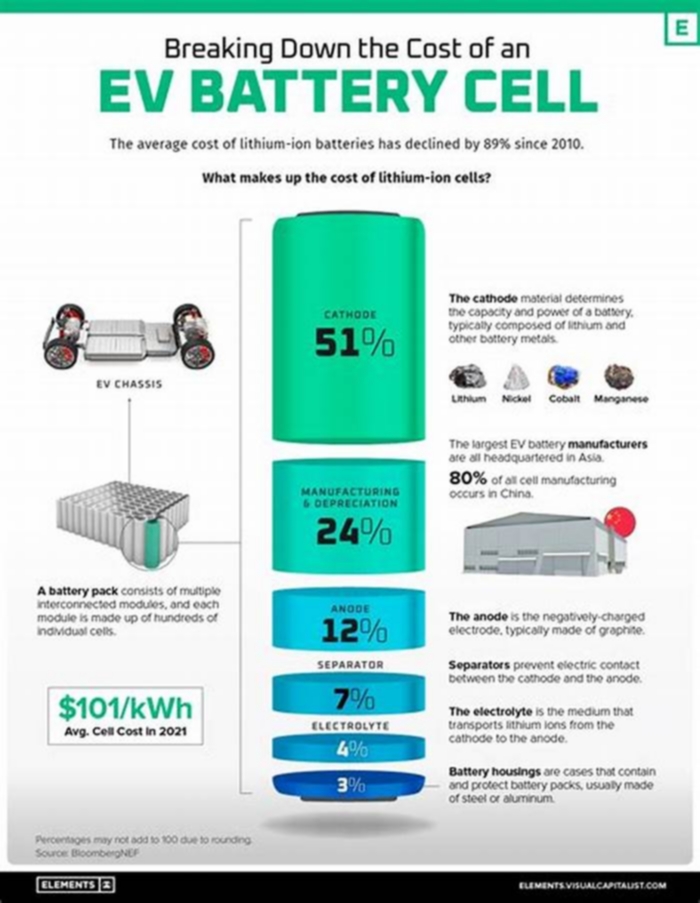

Not only do these batteries require large amounts of raw materials, including lithium, nickel and cobalt mining for which has climate, environmental and human rights impacts they also threaten to leave a mountain of electronic waste as they reach the end of their lives.

As the automotive industry starts to transform, experts say now is the time to plan for what happens to batteries at the end of their lives, to reduce reliance on mining and keep materials in circulation.

A second life

Hundreds of millions of dollars are flowing into recycling startups and research centers to figure out how to disassemble dead batteries and extract valuable metals at scale.

But if we want to do more with the materials that we have, recycling shouldnt be the first solution, said James Pennington, who leads the World Economic Forums circular economy program. The best thing to do at first is to keep things in use for longer, he said.

There is a lot of [battery] capacity left at the end of first use in electric vehicles, said Jessika Richter, who researches environmental policy at Lund University. These batteries may no longer be able run vehicles but they could have second lives storing excess power generated by solar or windfarms.

Several companies are running trials. The energy company Enel Group is using 90 batteries retired from Nissan Leaf cars in an energy storage facility in Melilla, Spain, which is isolated from the Spanish national grid. In the UK, the energy company Powervault partnered with Renault to outfit home energy storage systems with retired batteries.

Establishing the flow of lithium-ion batteries from a first life in electric vehicles to a second life in stationary energy storage would have another bonus: displacing toxic lead-acid batteries.

Only about 60% of lead-acid batteries are used in cars, said Richard Fuller, who leads the non-profit Pure Earth, another 20% are used for storing excess solar power, particularly in African countries.

Lead-acid batteries typically last only about two years in warmer climates, said Fuller, as heat causes them to degrade more quickly, meaning they need to be recycled frequently. However, there are few facilities that can safely do this in Africa.

Instead, these batteries are often cracked open and melted down in back yards. The process exposes the recyclers and their surroundings to lead, a potent neurotoxin that has no known safe level and can damage brain development in children.

Lithium-ion batteries could offer a less toxic and longer-lasting alternative for energy storage, Fuller said.

The race to recycle

When a battery really is at the end of its use, then its time to recycle it, Pennington said.

There is big momentum behind lithium-ion battery recycling. In its impact report, published in August, Tesla announced that it had started building recycling capabilities at its Gigafactory in Nevada to process waste batteries.

Nearby Redwood Materials, founded by the former Tesla chief technology officer JB Straubel, which operates out of Carson City, Nevada, raised more than $700m in July and plans to expand operations. The factory takes in dead batteries, extracts valuable materials such as copper and cobalt, then sends the refined metals back into the battery supply chain.

Yet, as recycling becomes more mainstream, big technical challenges remain.

One of which is the complex designs that recyclers must navigate to get to the valuable components. Lithium-ion batteries are rarely designed with recyclability in mind, said Carlton Cummins, co-founder of Aceleron, a UK battery manufacturing startup. This is why the recycler struggles. They want to do the job, but they only get introduced to the product when it reaches their door.

Cummins and co-founder Amrit Chandan have targeted one design flaw: the way components are connected. Most components are welded together, which is good for electrical connection, but bad for recycling, Cummins said.

Acelerons batteries join components with fasteners that compress the metal contacts together. These connections can be decompressed and the fasteners removed, allowing for complete disassembly or for the removal and replacement of individual faulty components.

Easier disassembly could also help mitigate safety hazards. Lithium-ion batteries that are not properly handled could pose fire and explosion risks. If we pick it down to bits, I guarantee you, its not going to hurt anyone, Cummins said.

Changing the system

Success isnt guaranteed even if the technical challenges are cracked. History shows how hard it can be to create well-functioning recycling industries.

Lead-acid batteries, for example, enjoy high rates of recycling in part due to legal requirements as much as 99% of lead in automobile batteries is recycled. But they have a toxic cost when they end up at improper recycling facilities. Spent batteries often end up with backyard recyclersbecause they can pay more for them than formal recyclers, who have to cover higher operating costs.

Lithium-ion batteries may be less toxic but they will still need to end up at operations that can safely recycle them. Products tend to flow through the path of least resistance, so you want to make the path which goes through formal channels less resistant, Pennington said.

Legislation could help. While the US has yet to implement federal policies mandating lithium-ion battery recycling, the EU and China already require battery manufacturers to pay for setting up collection and recycling systems. These funds could help subsidize formal recyclers to make them more competitive, Pennington said.

Last December, the EU also proposed sweeping changes to its battery regulations, most of which target lithium-ion batteries. These include target rates of 70% for battery collection, recovery rates of 95% for cobalt, copper, lead and nickel and 70% for lithium, and mandatory minimum levels of recycled content in new batteries by 2030 to ensure there are markets for recyclers and buffer them from volatile commodity prices or changing battery chemistries.

They arent in final form yet, but the proposals that are out there are ambitious, Richter said.

Data could also help. The EU and the Global Battery Alliance (GBA), a public-private collaboration, are both working on versions of a digital passport an electronic record for a battery that would contain information about its whole life cycle.

We are thinking about a QR code or a [radio frequency identification] detection device, says Torsten Freund, who leads the GBAs battery passport initiative. It could report a batterys health and remaining capacity, helping vehicle manufacturers direct it for reuse or to recycling facilities. Data about materials could help recyclers navigate the myriad chemistries of lithium-ion batteries. And once recycling becomes more widespread, the passport could also indicate the amount of recycled content in new batteries.

As the automobile industry starts to transform, now is the time to tackle these problems, said Maya Ben Dror, urban mobility lead at the World Economic Forum. The money pouring into the sector offers an opportunity to ensure that these investments are going to be in sustainable new ecosystems and not just in a new type of car, she said.

Its also worth noting that sustainable transport goes beyond electric cars, said Richter. Walking, biking or taking public transportation should not be overlooked, she said. Its important to remember that we can have a sustainable product situated within an unsustainable system.

What Happens to the Old Batteries in Electric Cars?

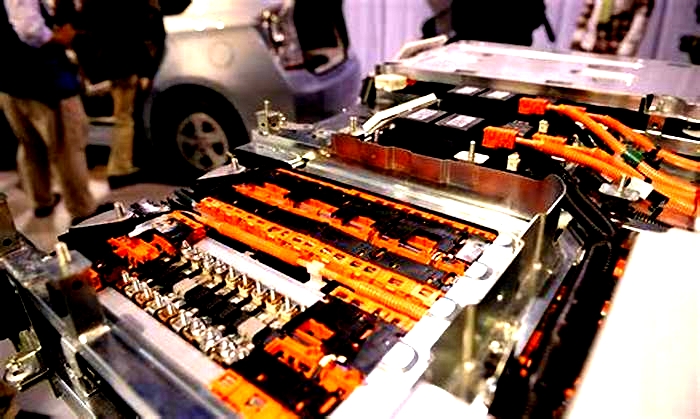

The worry for most environmentally conscious people is that there isnt a system in place to deal with these decommissioned parts. After all, lithium-ion battery packs often run the length of the cars wheelbase, weigh close to 1,000 pounds, and are made up of toxic elements. Can they easily be recycled or are they destined to pile up in landfills?

Electric car batteries arent very difficult to get rid of because even if theyve outlasted the usefulness for an electric car, theyre still worth quite a lot to someone, says Jake Fisher, Consumer Reports senior director of auto testing. Theres a strong demand for secondary-life batteries. Its not like when your gas-powered engine dies and it goes to the scrapyard. For example, Nissan is using old Leaf batteries to power mobile machines in its factories around the world.

Nissan Leaf batteries are also being used to store energy on solar grids in California, Fisher says. Once solar panels capture energy from the sun, they need to be able to store that energy. The old EV batteries may no longer be optimal for driving but theyre still capable of energy storage.

Even as secondary-life batteries fully degrade after various uses, minerals and elements like cobalt, lithium, and nickel in them are also valuable and can be used to produce new EV batteries.

With EV technology still in relative infancy, the only certainty is that recyclability needs to be built into the manufacturing process to ensure that EVs remain eco-friendly throughout the entire life cycle of the product.

Despite the concern about a potential costly repair when replacing these batteries, we havent seen it as a common issue in our exclusive car reliability data. Such problems are rare.

This article has been adapted from an episode ofTalking Cars.

Monthly Myth: Your EV battery mustbe replaced in 5 to 10 years

The battery in your electric car will last beyond its eight-year warranty. But given all the rampant battery life myths, how would you know that? Lets look at the facts.

At the heart of every vehicle is an energy source to drive the wheels. For internal combustion engines (ICE), its a tank of gas that burns to release required energy. For an electric vehicle (EV), itsa battery charged with electrons that providesenergy to an electric motor.

The myth

A gas tank is a hardy component that can be tricky to replace but is not terribly expensive. An EV battery is a large and complex subsystem formed to the underside of the vehicle in a skateboard-like configuration. Unlike gas tanks, batteries make up approximately 40 percent of the value of an electric car.

Therefore, prospective EV buyers are often concerned about the complexity, life span, and replacement cost of the battery. They hear it needs to be replaced in five to 10 years, but thats just not true. Lets myth-bust this one-by-one.

EVs arent like phones

Most people who have experience with smartphones are aware that lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries lose their capacity to hold charge over time. These folks worry that an EVs battery will behave in the same way. However unlike a smartphone, an EV battery consists of multiple AA-battery-like containersthat in most cases are supported by a Battery Management System. It automatically keeps the battery at an optimum temperature for a long life, at 70 degrees, where humans too are at their happiest.

An EVs batterys life can be maintained when it is not always charged to 100% and is not sitting empty for long. Most EVs have a user interface that informs the owner of the batterys charge level. Keeping an eye on the batterys health is a simple routine behavior for an EV owner.

EVs smart charge

Smartphone batteries are charged every day and degrade considerably after a few years. The average EV driver charges an EV just a few times per month. EVs also charge in a much smarter fashion, replenishing just depleted cells. This distributes the load across many thousands of cells that make up the whole battery.

Data gleaned from multiple Tesla owners has shown a mere 10% average battery degradation after over 160,000 miles. Most ICE cars are on the scrap heap long before they complete such mileage. Indeed, most people only keep their vehicles for approximately six years.

Cleaner sourcing extends use

More and more batteries are now manufactured from metals other than cobalt. These new metals not only last longer in batteries, they also address anxiety that prospective EV shoppers have had about the use of child labor in the cobalt mining process. In fact, the EV industry is more responsibly-sourced of late, and has a higher percentage of recycled components. The 2018 Tesla Model 3 battery consists of 2.9% cobalt. It is predicted that cobalt-free batteries could reach the market by 2025.

Interestingly, most plug-in vehicle makers are working with other battery types (such as lithium-iron-phosphate and lithium-manganese) which have inherent safety advantages and provide more years of service.

Used batteries see a second life

Another favorite anti-EV argument is that recycling Li-ion batteries is difficult, expensive or even flat-out impossible. However that is not the case. Recycling International reports that some 97,000 tons of Li-ion batteries were recycled in 2018, and over 1 GWh worth are currently serving in second-life applications.

500% less likely to catch fire

Finally, when news of an EV battery fire hits the headlines, fears are raised in the minds of buyers. To put the risk in perspective, UK data from 2019 obtained by Air Quality News revealed that the London Fire Brigade dealt with just 54 EV fires compared to 1,898 petrol and diesel fires.

Similarly, so far in 2020, London fire services have dealt with 1,021 petrol and diesel fires and just 27 EV fires.

As Elon Musk himself tweeted: Teslas, like most electric cars, are over 500% less likely to catch fire than combustion engine cars, which carry massive amounts of highly flammable fuels.

90% after 200k miles

Tesla's 2019 impact report showed that the majority of Model S and X cars had more than 90% battery life after 200,000 miles of driving.

Not surprisingly, the majority of manufacturers are so confident in the durability of their EV batteries that they offer a battery warranty thats usually 100,000 miles or eight years for 70% capacity. At the recent European Conference on Batteries, Elon Musk reported that batteries under development will give EVs 620 miles of range and a 15-year life. He also announced advances that will allow Tesla to slash battery manufacturing costs, speeding a global shift to renewable energy.

Conclusion

The facts show that EV batteries are very durable and warrantied for approximately eight years. Although range will degrade slightly over time, the battery will not need replacement for at least eight years, and will likely be totally acceptable for normal use far beyond that. Concerns about battery life should not dissuade potential buyers from purchasing an EV.

However, when they do get over this battery myth, these buyers may assume there are limited EV models to choose from. Next month well take a crack at that myth.