Why are people against electric cars

The red-state backlash against electric vehicles is incoherent and gaining steam

Remember when getting ICEd was a thing? A few years ago, it was not uncommon to spot internal-combustion engine (ICE) vehicles deliberately parked in electric vehicle-only spots, usually near an EV charging station, effectively blocking access to that charger. It was an extremely stupid and anti-social way for aggrieved gas-powered car owners to express contempt for these new, less-polluting vehicles.

Now a bunch of Republicans are taking the concept of getting ICEd to the next logical conclusion. Not content to simply obstruct a parking spot, they are instead looking to stymie the growth of EVs through ill-considered policy decisions. Their reasons are varied: some are trying to protect the oil and gas industry, while others simply want to stick it to Joe Biden or own the libs. But they are part of a growing trend of red states that are, in essence, parking their big, gas-powered vehicles in the path of progress.

Some are trying to protect the oil and gas industry, while others simply want to stick it to Joe Biden or own the libs

The latest example comes to us from Wyoming, where a group of Republican state lawmakers proposed a bill that would end EV sales by 2035. They characterize EVs as a misadventure that will gobble up massive amounts of electric power and threaten the incumbent oil and gas industry, which employs thousands of workers in the state.

The proliferation of electric vehicles at the expense of gas-powered vehicles will have deleterious impacts on Wyomings communities and will be detrimental to Wyomings economy and the ability for the country to efficiently engage in commerce,the bill reads. No mention is made of the deleterious impact of gas-powered vehicles through carbon emissions, nor the negative effects of extracting that gas from the land.

For a political party that purports to love freedom as much as they do, its a baffling position to actively seek to limit the purchasing choices of the American car buyer. And the bills lead sponsor seems to have only realized that in hindsight, telling The Washington Postthat he doesnt really want to do what the bill he introduced would actually do.

I dont have a problem with electric vehicles at all. Wyoming State Senator James Anderson told the paper. He said he didnt really want to ban EV sales, even though the bill he introduced is literally called Phasing out new electric vehicle sales by 2035.

Instead, Anderson claims he was just trying to send a message that were not happy with the states that are outlawing our vehicles a reference to California and others that have proposed phasing out the sale of gas-powered vehicles.

For a political party that purports to love freedom as much as they do, its a baffling position to actively seek to limit the purchasing choices of the American car buyer

Performative politics can get you headlines, but it can also cost your state a lot of jobs. Take Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin, for example, who just put the kibosh on a proposed Ford battery plant in his state because of the involvement of a Chinese company.

Ford pitched building a $3.5 billion factory in one of the poorest parts of Virginia, part of a swath of new battery plants across the Deep South. The project would have created up to 2,500 new jobs building lithium iron phosphate batteries for Fords electric vehicles.

But Youngkin intervened because of the involvement of CATL, a Chinese battery manufacturer and one of the biggest producers of EV batteries in the world. While Ford is an iconic American company, it became clear that this proposal would serve as a front for the Chinese Communist party, which could compromise our economic security and Virginians personal privacy, a spokesperson for the governor told The Richmond Dispatch.

Calling CATL a front for the CCP is overly simplistic. The battery company isnt state-owned, but it does benefit from lavish subsidies and a soft regulatory environment from Beijing that has helped fuel its growth globally. Chinese companies have cornered the market on EV batteries a fact that will likely make it extremely difficult to realize the benefits of the Inflation Reduction Acts EV tax credit, which requires battery materials to be sourced from North America. (Or not? TBD.)

Performative politics can get you headlines, but it can also cost your state a lot of jobs

There is a long history of politicians cutting off their nose to spite their face, but Youngkin seems determined to obstruct economic growth in his own state to appear more anti-China than his rivals as he vies for the Republican nomination for president in 2024.

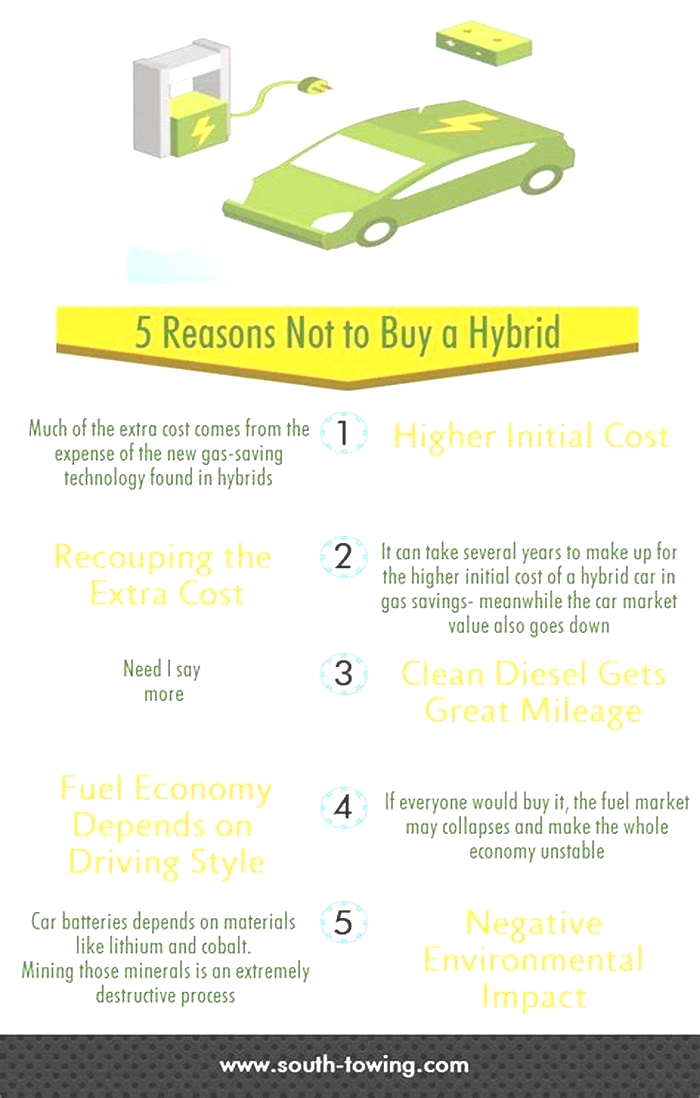

To be sure, there is little coherence to the backlash against EVs. Its a melange of anti-Biden / anti-California posturing mixed with concern trolling over the environmental impact of mining for battery minerals (a real issue but less detrimental to the environment than the collective tailpipe emissions of all our cars), with a dash of grievance politics over socialist state governments dictating what kind of car youre allowed to buy. Tucker Carlson hit all these points in a rambling segment last year, in which he called EVs terrible for the environment while also managing to bash California Governor Gavin Newsom for his use of a private jet.

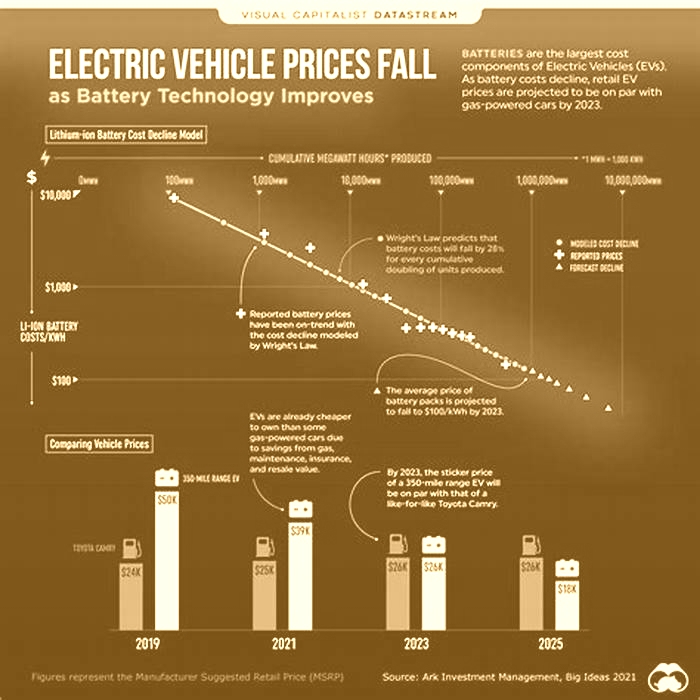

For over a century, car buyers have only had one choice. It was ICE all down the line. And now that theres finally a new option electric powertrains right-wing media and politicians are trying to muddy the waters by branding EVs as the vehicle choice for the elite. Its not a difficult task: EVs are expensive, and sales tend to be concentrated in liberal states. But that is changing as more companies release new models with more affordable price tags and more conservative-friendly pedigrees (see: Ford F-150 Lightning, Chevy Silverado EV, and GMC Sierra EV).

Its unclear whether Republicans stand to gain anything from all their posturing. A broad swath of Americans support incentives for EVs but are on the fence as to whether they would buy one themselves. And on the question of phasing out the sale of gas-powered vehicles, the political divide is stark: Democrats largely support such policies, while Republicans do not.

To be sure, there is little coherence to the backlash against EVs

Not every Republican is so short-sighted as to turn down a good opportunity when it presents itself. They may not be outright supportive of efforts to phase out gas-car sales, but they are eager to promote and expand the EV industry. Indianas Republican governor, for example, has sponsored research, traveled to Asia to spur business, and handed out millions of taxpayer dollars to manufacturers, according to Yahoo.

They want the economic benefits of a growing industry but still want to be seen by their constituents as sticking it to their opponents. Indianas attorney general is one of 14 Republican AGs who have sued the Biden administration seeking to block Californias right to set its own emissions standards.

And then theres Elon Musk, the king of EV sales whose acquisition of Twitter and online antics have weirdly done more to soften conservative backlash against EVs than anyone else. Its doubtful that Republicans will champion his efforts to decarbonize transportation as readily as they do his commitment to free speech online, but at best, his new prominence among conservatives will complicate their feelings towards EVs. (As my colleague Liz Lopatto has so ably pointed out, Musks public persona seems disproportionately influenced by Texas Republicans, whom he relies on for subsidies for his companies.)

It was inevitable that EVs would get sucked into our larger culture wars. But its unlikely that a few scattered Republicans can derail the momentum that EVs have been building over the past few years. It would be nice if their objections centered on real concerns, like the need to reduce driving overall, or the worrisome trend in big, heavy EVs requiring obnoxiously heavy batteries. You really want to own the libs? How about legislating against the Biden-approved Hummer EV?

Theres One Big Problem With Electric Cars

I am starting to worry about the electric car.

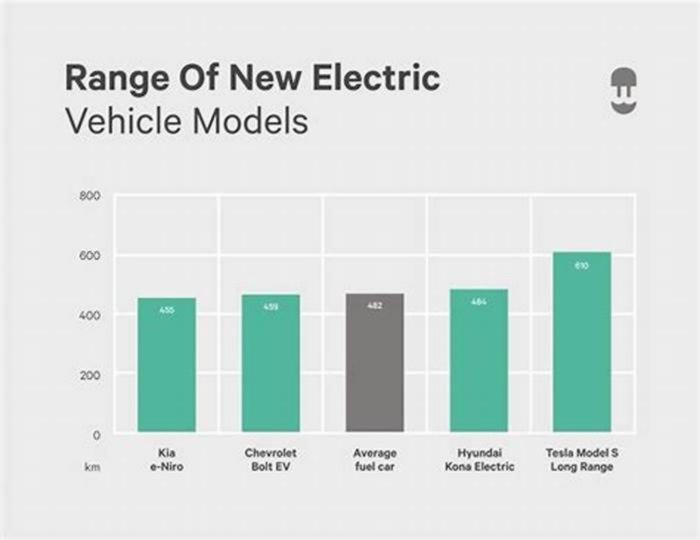

Not the thing itself; Ive found electric vehicles to be superior to their fossil-powered predecessors in just about every important way, and although I am a car-crazy Californian, I dont expect to buy a lung-destroying, pollution-spewing gas car ever again.

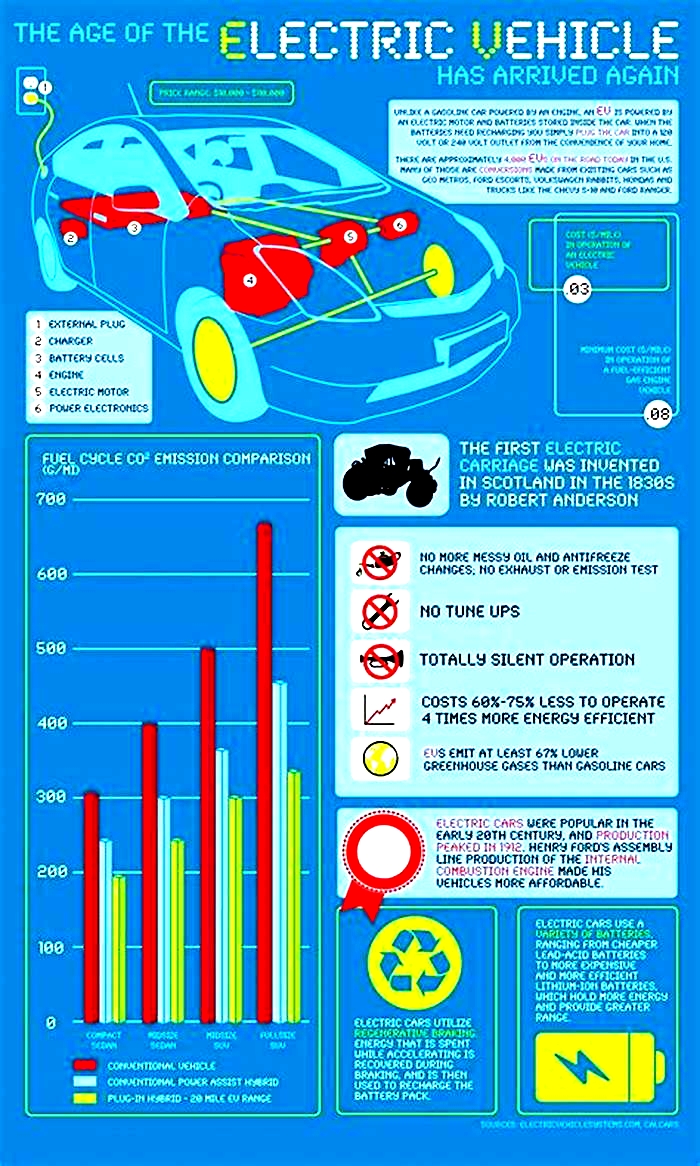

But electric motors are merely a power source, not a panacea. From General Motors Super Bowl ads to President Bidens climate-change plans, plug-in cars are now being cast as a central player in Americas response to a warming future turning a perfectly reasonable technological hope into overblown hype.

The planet will be much better off if we switch to electric cars. But gauzy visions of the guilt-free highways of tomorrow could easily distract us from the larger and more entrenched problem with Americas transportation system.

That problem isnt just gas-fueled cars but car-fueled lives a view of the world in which huge private automobiles are the default method of getting around. In this way E.V.s represent a very American answer to climate change: To deal with an expensive, dangerous, extremely resource-intensive machine that has helped bring about the destruction of the planet, lets all buy this new version, which runs on a different fuel.

But while we go about the project of building electric cars into tomorrows infrastructure Biden has pledged to create a network of 500,000 charging stations around the country and replace the roughly 650,000 cars in the federal governments fleet with E.V.s lets not overlook a more immediate menace on the roads today. I refer to the millions of big, inefficient trucks and S.U.V.s that are Americas favorite cars, each poisoning our atmosphere for years beyond any transition to E.V.s.

The promise of electric cars grants us a little leeway to party on in the gas-guzzling present E.V.s offer a politically simple, one-stop expiation for our unsustainable ways, so long as we all ignore the Escalade in the room.

Fixing the problems caused by cars with new and improved cars and expensive new infrastructure just for cars illustrates why were in this mess in the first place an entrenched culture of careless car dependency. Liberation from car culture requires a more fundamental reimagining of how we get around, with investments in walkable and bike-able roadways, smarter zoning that lets people live closer to where they work, a much greater emphasis on public transportation and above all a recognition that urban space should belong to people, not vehicles. Policy changes that reduce the amount Americans drive could lead to far greater efficiency gains than wed get just from switching from gas to batteries.

During his time as mayor of South Bend, Ind., Pete Buttigieg, the new secretary of transportation, advocated plans to reduce car dependency. But asking Americans to begin to imagine a future of fewer, smaller cars and less driving will be a great political heave. I can already imagine the Fox News segments pillorying Biden and Mayor Pete for their war on S.U.V.s and pickup trucks.

I too might sound like a mirthless environmental scold. But perhaps we all need a little scolding.

Between 2009 and 2019, the average fuel economy across all vehicles increased only slightly, according to data from the Environmental Protection Agency. Our cars were getting an average of 22.4 miles per gallon in 2009, and by 2019 efficiency had grown to 24.9 m.p.g., a gain of about 11 percent.

We could have done much better, with efficiency rising perhaps as much as 4 percent or 5 percent a year, John DeCicco, a research professor emeritus at the University of Michigan Energy Institute, told me. After fuel economy standards were raised under George W. Bush and then even more under Barack Obama, manufacturers began installing a host of new technologies to make cars more efficient. Most vehicle types became significantly cleaner average fuel economy for sedans, for instance, grew to 30.9 m.p.g. in 2019 from 25.3 m.p.g. in 2009, a gain of about 22 percent.

So how did most cars get so much better without changing the bigger picture very much at all? Its simple, DeCicco says: We ate our gains.

As cars became more efficient, people began buying larger, heavier and more powerful cars. In particular, we got hooked on sport utility vehicles and those formless blobs on wheels known as crossovers, which became one of the hottest segments of the car business. A decade ago, about half of all cars sold were sedans, which are some of the most efficient vehicles on the road, and about a quarter were S.U.V.s, which are some of the least efficient. By 2019 only a third of cars sold were sedans, and about half were small or large S.U.V.s. Given more efficient cars, we bought more car.

Federal policy hasnt helped. In 2017 the Trump administration began to undo Obamas fuel rules, a reversal that fostered uncertainty and division in the car industry and perhaps pushed carmakers to lay off new fuel-saving technologies.

The growing adoption of electric vehicles over the last decade did little to counteract these larger forces; any environmental benefits we got from zero-emission E.V.s were swamped by the much larger market shift toward bigger cars. While electric cars are important, DeCicco wrote recently on his blog, much more stringent clean car standards are the real priority for putting the U.S. automobile fleet on track for climate protection.

Naturally, the car industry is not in favor of significantly stricter fuel standards. Carmakers expect Biden to raise fuel standards, but they are pushing for something less than the Obama rules, which would have required passenger vehicles to achieve an average of 54.5 m.p.g. by 2025.

Among environmentalists, there is more than a little suspicion that the flurry of new electric vehicle announcements including G.M.s pledge to sell only zero-emission passenger cars by 2035 is a negotiating tactic to forestall very tough fuel standards. Carmakers will gladly give us some awesome E.V.s tomorrow for lenient rules today.

Theres a chance Im being overly cynical. To the car industrys credit, the push for electric vehicles does appear to be real. Carmakers are investing hundreds of billions of dollars to bring about the electric future, and in the next few years they plan to release dozens of electric models. Ford, for instance, is pumping electrons into its most iconic models an electric Mustang, the Mach-E, was just introduced to positive reviews, and the F-150 pickup truck, for decades the best-selling vehicle in America, will be offered in an electric version next year.

But its worth remembering that the electric future is still just a vision, not a certainty. The car industrys electric dreams are fueled by a singular success Tesla, Elon Musks electric-car juggernaut. In a pandemic-crushed market otherwise brutal for the car industry, Tesla shipped just shy of half a million vehicles in 2020, about a third more than it sold in 2019.

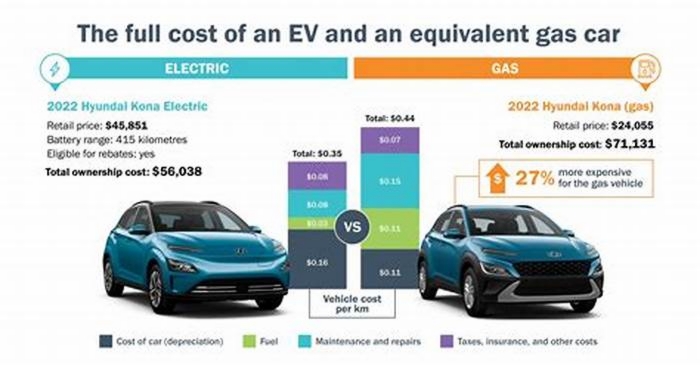

But no other carmaker has found much luck in electric vehicles, and serious questions about the business remain. Will E.V.s become cheap and convenient enough to attract a mainstream audience? Can carmakers that now rely on big pickups and S.U.V.s for their profits make money on the electric models? How should we address the inequities in the market? At the moment, electric cars are still pricier than gas-powered alternatives, and the $7,500 federal credit on their sales is essentially a subsidy for rich people. Is that the best use of transportation funds?

And what do we do about gas-powered cars? You may have seen that bizarre G.M. Super Bowl ad in which Will Ferrell and his celebrity pals invade Norway because it has been wildly successful at selling electric vehicles. What the ad doesnt mention is the reason so many Norwegians are buying E.V.s: The country has imposed steep taxes on gas-powered cars, accelerating the transformation to a cleaner future. Should we follow its lead?

All of these questions will affect the viability of the electric car business. Note that even Tesla has never made a profit just by selling cars. The company has amassed oodles of zero-emission regulatory credits that it sells to other carmakers; in 2020, Tesla brought in more than $1.6 billion through credits, without which its business would have posted a net loss.

Then there are all the problems with cars that electric motors wont fix. Cars have insatiable demand for roadway and urban space, capturing our cities for their near-exclusive use. They are expensive and inefficient the ridiculous notion of paying thousands of dollars a year for a machine thats mostly parked is no less ridiculous because the car is being charged while its parked. And whether our cars are powered by electrons or petroleum, its likely that more than a million people around the world will keep dying in crashes every year.

Can we fix these issues with more advanced tech? Perhaps, someday. But wed make better progress if we identified the correct problem: not gas, but cars.

Office Hours With Farhad Manjoo

Farhad wants to chat with readers on the phone. If youre interested in talking to a New York Times columnist about anything thats on your mind, please fill out this form. Farhad will select a few readers to call.