Why hybrids are better than EV

How-To Geek

Are you in the market for a new car? Gas prices are rough and electric cars can be expensive, but there's good news: Hybrid cars aren't just less expensive---they may actually be better than fully electric cars in today's world.

Hybrids Are the Perfect Compromise (for Now)

This article isn't about attacking electric cars. Affordable zero-emissions electric cars served by a widespread infrastructure of charging stations---all powered by inexpensive clean energy---is the dream. It's a world we'd like to see.

But electric cars have some serious issues as of 2022. They can be much more expensive than gas cars, and that new EV credit in the Inflation Reduction Act is pretty complicated. Even if you could afford them, you're dependent on charging stations that just aren't as widespread as gas stations. (They're more widespread in some areas than others.) And how are you supposed to charge an electric car at night if you live in an apartment complex without chargers or have to park on a street?

Likewise, traditional gasoline-powered cars have the obvious advantages of being less expensive up front and being able to refuel at widespread gas stations. But, while they're cheaper to buy, you'll be paying at the pump. Gas prices have gone down somewhat from their peak in 2022, but who knows what will happen in the future. (Of course, emissions are a real concern---but there's a strong enough argument for avoiding traditional gasoline-powered cars just based on personal interest alone!)

That's why you should give hybrids a look. Hybrids combine many of the advantages of electric cars with many of the advantages of gasoline-powered cars.

That said, if you're excited about paying top dollar for an electric car and you know the recharging experience is going to work for you, go right ahead! This article is for the rest of us---those who balk at the high cost of electric cars and wonder if the traditional gas-powered car is a better option. There's a third way.

So, About That Expensive Electric Vehicle's Range...

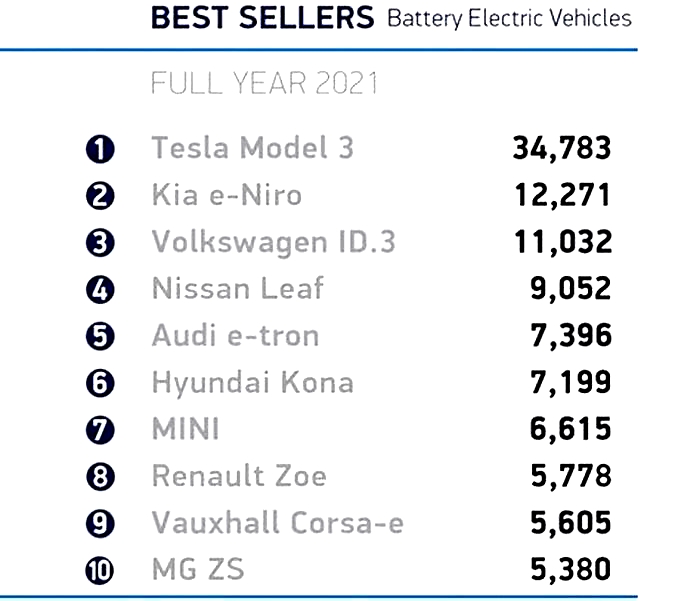

Let's talk price and how it compares to range. As of September 14, 2022, here's a look at the prices of some new electric cars and their range on a charge.

You can get more range from some of these cars, but you'll have to pay extra for a model with a bigger battery. The Mazda MX-30's range is shockingly low---only 100 miles. Meanwhile, there are other gotchas: The Nissan LEAFstill uses CHAdeMO for Level 3 charging, meaning it will be much harder to find charging stations where you can charge it at top speeds in the U.S.

Related: Level 1, Level 2, or Level 3? EV Chargers Explained

If you're going longer than that, you'll have to find an EV charger on the way. Once you're at the charger, how long it takes to charge your EV will depend on a wide variety of factors, including your car and the charger type you have available. A Level 3 chargercan typically charge a vehicle to 80% in a half hour or so.

Hybrids Offer the Longest Range and Easier Refueling

Hybrids are significantly cheaper than electric cars. You can generally expect somewhere between 48 and 60 miles per gallon, although a truck will, of course, offer fewer miles per gallon than a sedan.

For example, the 2022 Hyundai Sonata Hybrid starts at $27,350, gets 52 miles per gallon, and has a 13.2-gallon gas tank. That means this car has a686-mile range when its gas tank is full.

Do the math: You can go nearly three times the distance as an electric car before you have to refill a hybrid like this. When it's time to refuel, you can stop at any gas station and quickly refill the tank. You don't have to ensure you reach a charging station on your current range and sit there waiting to recharge.

And, if you don't have a place to plug in the car at your work or home, that's fine---you just have to stop at a gas station once every 600+ miles.

It goes without saying that a traditional gas-powered car is much less efficient than a hybrid with a battery. Comparing apples to apples, the 2022 Hyundai Sonata (non-hybrid) gets 32 miles per gallon and starts at $24,500.

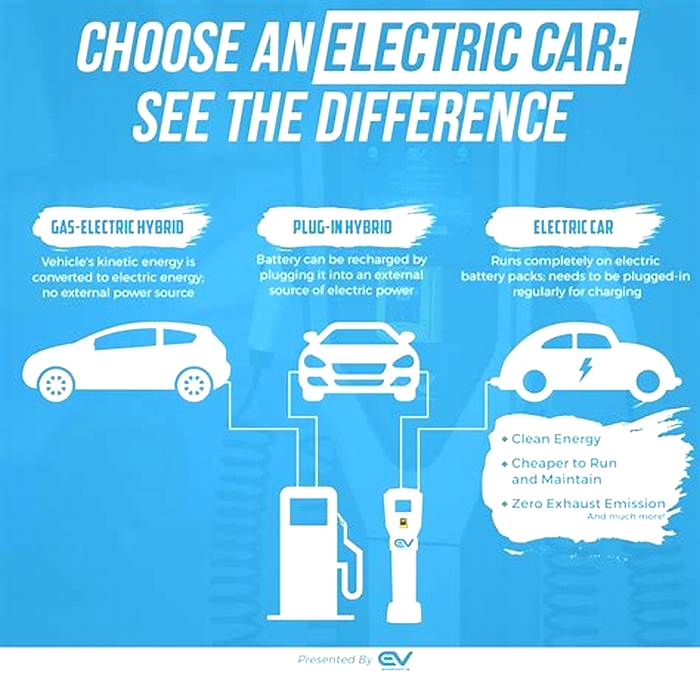

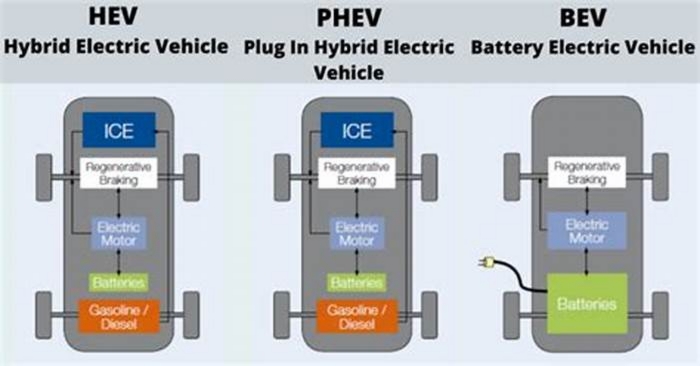

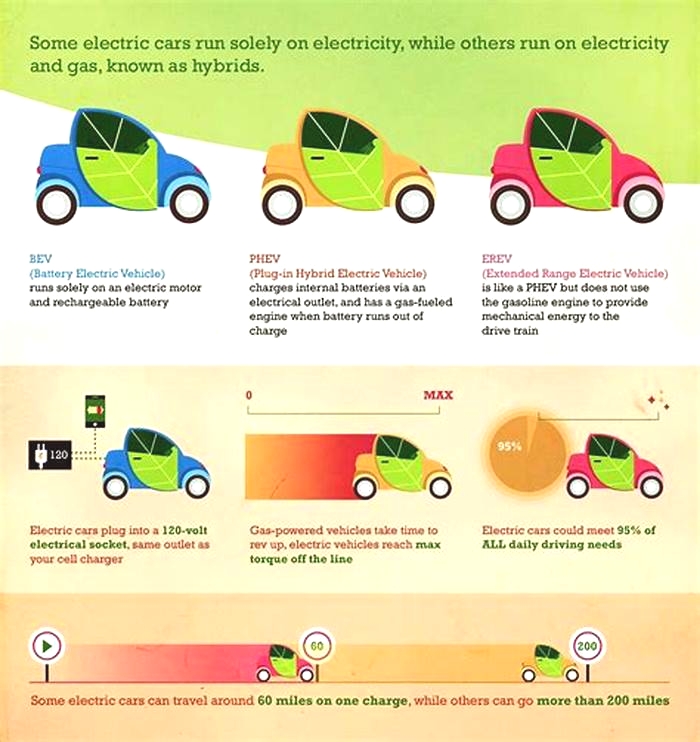

Related: Electric Cars vs. Hybrids: What's the Difference?

This is just one example of a hybrid---there are many other great hybrid cars out there, and we're not recommending one manufacturer over another here.

A Plug-in Hybrid Might Be an Even Better Idea

Plug-in hybrids are another great idea. Take the 2022 Toyota Prius Prime, for example. It's a plug-in hybrid with a $28,770 starting price. If you plug it in to charge, it can get 25 miles of range in EV mode before using gas.

If your daily commute is 10 miles each way, you could charge your car at home every night and never use gas on your commute---not unless you need to go any further. If you do go further, your car will use its gas tank.

You're never forced to find a charger. You can plug a plug-in hybrid if you want, but it'll work as a normal gas-powered hybrid if you don't. A plug-in hybrid gives you that option.

There are other plug-in hybrids that get you between 30 and 40 miles of electric range, too. Again, we're not recommending one particular manufacturer here.

Plug-in hybrids seem like an important part of the future. They can help make day-to-day errands and commuting possible over electricity without the massive batteries, range anxiety, or any charging infrastructure at all beyond your own garage.

Related: California Plans to Block Sales of New Gas Cars by 2035

Even California's much-publicized plan to ban gasoline-powered cars by 2035 includes an exception for plug-in hybrids, which will still be allowed.

Hybrids: Better Than EVs?

Which vehicle you buy is an incredibly personal choice. But, as we've seen, there's a very strong argument for hybrid vehicles in the early 2020s. They're not just cheaper than electric cars: They're arguably more convenient and flexible.

We hope that will change going forward as electric charging infrastructure becomes more widespread and EVs become more affordable. Until then, there's good news: Even if you can't justify buying an expensive electric car, those less expensive hybrids might be even better.

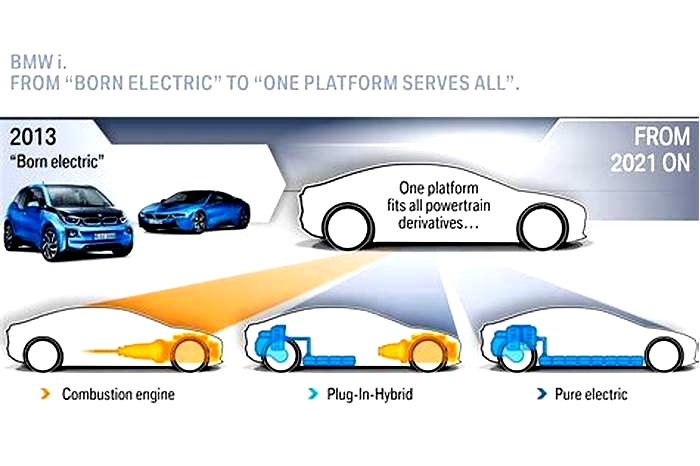

Toyota Is Right: We Need More Hybrid Cars and Fewer EVs. Heres Why

It sounds like heel-dragging from a latecomer whose first electric car was met with a lukewarm reception. But if you take a closer look at how efficiently hybrids and EVs use their batteries, youll realize Toyota is actually right: hybrids have a bigger role to play in decarbonization than EVs will for a long time, if ever. Fact is, we need to use our limited battery supplies to deliver the maximum reduction in CO2 emissions across the auto industry, and soon. We need to use every last kilowatt-hour to its fullest, and in the near-term, that doesnt mean going all-in on EVs. It means leaning back into hybrids.

Whats more, EV battery supplies are expected to fall short of demand within the next couple of years. Benchmark Mineral Intelligence told The Financial Times it forecasts lithium demand growing fivefold by 2035, while Boston Consulting Group predicts chronic shortages as soon as 2025. Last year, Stellantis CEO Carlos Tavares warned of similar in CNBC, foretelling mineral and battery shortages later this decade.

So is there a better use for the batteries currently being crammed into a relatively small number of $60,000 electric sedans or $100,000 electric pickups? Could switching to full-hybrid model lineupsnow mostly dismissed as a temporary bridgeactually reduce emissions quicker than fast-tracking EVs in the short term?

The Case for Hybrids Over EVs

To illustrate, we're going to compare the on-road carbon emissions of a few models that are available with internal combustion, hybrid/plug-in hybrid (PHEV), and electric powertrains: the Ford F-150, the 2022 Hyundai Kona and Kia Niro (which use the same chassis) and the BMW 3 Series and i4 (which also share their bones). Again, this is the question we want to answer: Whats the best use of a limited battery supply? Do we spread those materials across a bunch of hybrids, or cram them into a few EVs and leave the remainder with straight gas or diesel engines?

We can answer this by dividing how much each vehicle reduces CO2 emissions over its ICE counterpart by its battery capacity in kilowatt-hours. Thats tricky to imagine, so dont bother: just look at this equation instead.

We need more data to fill that out, of course, and obtaining it is simple: The EPAs FuelEconomy.gov publishes per-mile CO2 estimates, which also estimate the upstream emissions that come from gasoline production.

Things arent as straightforward for EVs, though, which the EPA lists as emitting no CO2. While true from an exhaust standpoint, making the electricity needed to charge them does generate CO2: an average of 386 grams of it per kWh in the United States, according to the Energy Information Administration. We can then estimate their hidden CO2 emissions with the equation illustrated below. (Its the same formula we used to calculate the break-even point for EVs when it comes to charging and production emissions vs their on-road savings last year.)

Armed with this data, we can then calculate how efficiently each electrified vehicle uses its battery. The equation well use for that is shown aboveremember, the goal is to reduce CO2 emissions as much as possible with a limited supply of batteries. And when you do the math, its pretty clear what the best option is.

Consider just how much battery your typical mass-market EV uses. Operating an F-150 Lightning may generate less than a third of the CO2 emissions of a gas F-150, but each one hoards 98 kWh of battery, most of which will be used only on the rare prolonged drive. Meanwhile, an F-150 Powerboost hybrid battery is just 1.5 kWh. It doesnt achieve nearly the emissions reduction the Lightning does, but Ford could make 65 of them with the batteries that go into a single Lightning.

That adds up, because if Ford sells one Lightning and 64 ICE F-150s, its cutting the on-road CO2 emissions of those trucks as a group by 370 g/mi. If it sold 65 hybridsspreading the one Lightnings battery supply across them allitd reduce aggregate emissions by 4,550 g/mi. Remember, this is using the exact same amount of batteries; the distribution is just different.

The pattern holds true for the Hyundai/Kia combo and the BMWs, toogoing full hybrid lowers emissions far more than building a handful of EV and a ton of gas cars. Split up an i4s battery, and you can make seven 330e PHEVs, cutting 560 g/mi to one i4s 266. Divvy up a Kona EVs, and you can make seven Niro PHEVs worth 1,085 g/mi in reductions (one EVs worth 239), or 41 regular Niro hybrids, for 4,797 g/mi eliminated. Like the Ford, they make better use of a fixed battery supply by spreading it across a large number of hybrids, rather than concentrating them all in a single EV.

Of course, EVs cases improve when theyre run exclusively on renewable energy. We can zero their per-mile CO2 emissions to simulate that, and it helps them outbut it doesnt change the fact that their battery use is still inefficient. Powering a handful of EVs with renewables still just doesnt have the immediate effect that a broader hybridization of new cars would.

It comes down to this: By using its limited battery supply on a small number of (expensive) EVs, the auto industry gets plaudits from investors and the public despite implementing an inefficient decarbonization scheme. It gets to greenwash itself with a handful of flashy products, while in fact not cutting CO2 emissions nearly as much as it could. The numbers strongly suggest that hybridizing as many new cars as possible is more effective, and to increasing degrees as battery technology evolves and supplies hopefully go up. That would allow hybrids to graduate to PHEVs, before being superseded by full EVs where appropriate.

Most of the benefits of a full EV transition, however, would present themselves with widespread PHEV adoption. They offer enough range to make short trips on electric power alone, often at comparable up-front cost to an EV, but also the flexibility and efficiency of a hybrid powertrain for longer journeys. This lets them sidestep most of the obstacles to EV adoption, namely battery supply and poor charging infrastructure.

That said, there are reasons why PHEVs havent taken off. Theyre less efficient and more complicated to produce and service than EVs or regular hybrids, not to mention heavier and more expensive than regular hybrids. Theyre also not helped by their confusing names, never mind the PHEV acronym.

Hybrids as a whole have taken a long time to capture market share, accounting for just 5.5 percent of the light vehicle market in 2021, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Thats over a period of 24 years since the pioneering Toyota Prius entered production. EVs meanwhile achieved a similar market share in less than half that time, attaining 5.8 percent of the U.S. market in 2022 according to The Wall Street Journal. Thats only a decade since the paradigm-shifting Tesla Model S entered production.

So far, the government has favored the shiny, hype-driven solution of fast-tracking EV adoption, when the math suggests thats suboptimalat least for the short and medium term. If anything, its probably fair to say the over-emphasis on EVs is slowing the decarbonization of the auto industry for the time being. We cant afford to overlook the role hybrids have to play here and now in favor of a far-flung future where every car on the road is pure electric.

Besides, when the 2023 Toyota Prius is one of the best-looking cars on sale today, it makes the pragmatic solution that much easier to choose.

Got a tip or question for the author? You can reach them here: [email protected]