Why hydrogen cars are not the future

The Future of Hydrogen

The time is right to tap into hydrogens potential to play a key role in a clean, secure and affordable energy future.At the request of the government of Japan under its G20 presidency, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has produced this landmark report to analyse the current state of play for hydrogen and to offer guidance on its future development. The report finds that clean hydrogen is currently enjoying unprecedented political and business momentum, with the number of policies and projects around the world expanding rapidly. It concludes that now is the time to scale up technologies and bring down costs to allow hydrogen to become widely used. The pragmatic and actionable recommendations to governments and industry that are provided will make it possible to take full advantage of this increasing momentum.

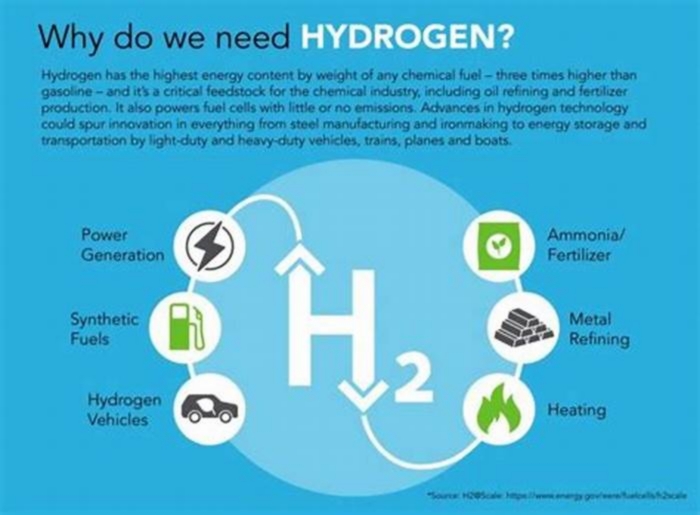

Hydrogen can help tackle various critical energy challenges.It offers ways to decarbonise a range of sectors including long-haul transport, chemicals, and iron and steel where it is proving difficult to meaningfully reduce emissions. It can also help improve air quality and strengthen energy security. Despite very ambitious international climate goals, global energy-related CO2emissions reached an all time high in 2018. Outdoor air pollution also remains a pressing problem, with around 3million people dying prematurely each year.

Hydrogen is versatile.Technologies already available today enable hydrogen to produce, store, move and use energy in different ways. A wide variety of fuels are able to produce hydrogen, including renewables, nuclear, natural gas, coal and oil. It can be transported as a gas by pipelines or in liquid form by ships, much like liquefied natural gas (LNG). It can be transformed into electricity and methane to power homes and feed industry, and into fuels for cars, trucks, ships and planes.

Hydrogen can enable renewables to provide an even greater contribution.It has the potential to help with variable output from renewables, like solar photovoltaics (PV) and wind, whose availability is not always well matched with demand. Hydrogen is one of the leading options for storing energy from renewables and looks promising to be a lowest-cost option for storing electricity over days, weeks or even months. Hydrogen and hydrogen-based fuels can transport energy from renewables over long distances from regions with abundant solar and wind resources, such as Australia or Latin America, to energy-hungry cities thousands of kilometres away.

There have been false starts for hydrogen in the past; this time could be different.The recent successes of solar PV, wind, batteries and electric vehicles have shown that policy and technology innovation have the power to build global clean energy industries. With a global energy sector in flux, the versatility of hydrogen is attracting stronger interest from a diverse group of governments and companies. Support is coming from governments that both import and export energy as well as renewable electricity suppliers, industrial gas producers, electricity and gas utilities, automakers, oil and gas companies, major engineering firms, and cities. Investments in hydrogen can help foster new technological and industrial development in economies around the world, creating skilled jobs.

Hydrogen can be used much more widely.Today, hydrogen is used mostly in oil refining and for the production of fertilisers. For it to make a significant contribution to clean energy transitions, it also needs to be adopted in sectors where it is almost completely absent at the moment, such as transport, buildings and power generation.

However, clean, widespread use of hydrogen in global energy transitions faces several challenges:

- Producing hydrogen from low-carbon energy is costly at the moment. IEA analysis finds that the cost of producing hydrogen from renewable electricity could fall 30% by 2030 as a result of declining costs of renewables and the scaling up of hydrogen production. Fuel cells, refuelling equipment and electrolysers (which produce hydrogen from electricity and water) can all benefit from mass manufacturing.

- The development of hydrogen infrastructure is slow and holding back widespread adoption.Hydrogen prices for consumers are highly dependent on how many refuelling stations there are, how often they are used and how much hydrogen is delivered per day. Tackling this is likely to require planning and coordination that brings together national and local governments, industry and investors.

- Hydrogen is almost entirely supplied from natural gas and coal today.Hydrogen is already with us at industrial scale all around the world, but its production is responsible for annual CO2emissions equivalent to those of Indonesia and the United Kingdom combined. Harnessing this existing scale on the way to a clean energy future requires both the capture of CO2from hydrogen production from fossil fuels and greater supplies of hydrogen from clean electricity.

- Regulations currently limit the development of a clean hydrogen industry.Government and industry must work together to ensure existing regulations are not an unnecessary barrier to investment. Trade will benefit from common international standards for the safety of transporting and storing large volumes of hydrogen and for tracing the environmental impacts of different hydrogen supplies.

The IEA has identified four near-term opportunities to boost hydrogen on the path towards its clean, widespread use. Focusing on these real-world springboards could help hydrogen achieve the necessary scale to bring down costs and reduce risks for governments and the private sector. While each opportunity has a distinct purpose, all four also mutually reinforce one another.

- Make industrial ports the nerve centres for scaling up the use of clean hydrogen.Today, much of the refining and chemicals production that uses hydrogen based on fossil fuels is already concentrated in coastal industrial zones around the world, such as the North Sea in Europe, the Gulf Coast in NorthAmerica and southeastern China. Encouraging these plants to shift to cleaner hydrogen production would drive down overall costs. These large sources of hydrogen supply can also fuel ships and trucks serving the ports and power other nearby industrial facilities like steel plants.

- Build on existing infrastructure, such as millions of kilometres of natural gas pipelines.Introducing clean hydrogen to replace just 5% of the volume of countries natural gas supplies would significantly boost demand for hydrogen and drive down costs.

- Expand hydrogen in transport through fleets, freight and corridors.Powering high-mileage cars, trucks and buses to carry passengers and goods along popular routes can make fuel-cell vehicles more competitive.

- Launch the hydrogen trades first international shipping routes.Lessons from the successful growth of the global LNG market can be leveraged. International hydrogen trade needs to start soon if it is to make an impact on the global energy system.

International cooperation is vital to accelerate the growth of versatile, clean hydrogen around the world.If governments work to scale up hydrogen in a coordinated way, it can help to spur investments in factories and infrastructure that will bring down costs and enable the sharing of knowledge and best practices. Trade in hydrogen will benefit from common international standards. As the global energy organisation that covers all fuels and all technologies, the IEA will continue to provide rigorous analysis and policy advice to support international cooperation and to conduct effective tracking of progress in the years ahead.

As a roadmap for the future, we are offering seven key recommendations to help governments, companies and others to seize this chance to enable clean hydrogen to fulfil its long-term potential.

Why is hydrogen no longer the fuel of the future?

6 mins read26 January 2022

Hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) should be making their big stage entrance right about now. Petrol and diesel cars are under fire as the UK government pushes harder for zero emissions ahead of its ban on new ICE vehicles from 2030.

Meanwhile, hydrogen is a key part of emissions reduction from British power generation (plans were announced last year to produce 5GW worth annually by 2030 roughly the output of two nuclear plants).

To access this content please subscribe

Already registered?

Login 20% annual savingRegular membership

Automatic renewal

Team membership

799

Price includes a 20% discount for a team of 5

Will hydrogen overtake batteries in the race for zero-emission cars?

Hydrogen is a beguiling substance: the lightest element. When it reacts with oxygen it produces only water and releases abundant energy. The invisible gas looks like a clean fuel of the future. Some of the worlds top automotive executives are hoping it will dethrone the battery as the technology of choice for zero-emissions driving.

Our EV mythbusters series has looked at concerns ranging from car fires to battery mining, range anxiety to cost concerns and carbon footprints. Many critics of electric vehicles argue that we should not ditch petrol and diesel engines. This article asks: could hydrogen offer a third way and overtake the battery?

The claim

Many of the strongest claims for hydrogens role in the automotive world come from chief executives at the heart of the industry. Japans Toyota is the most vocal proponent of hydrogen, and its chair, Akio Toyoda, last month said he believed the share of battery cars would peak at 30%, with hydrogen and internal combustion engines making up the rest. Toyotas Mirai is one of the only hydrogen-powered cars that is widely available, alongside the Nexo SUV from South Koreas Hyundai.

Oliver Zipse, the boss of the German manufacturer BMW, said last year: Hydrogen is the missing piece in the jigsaw when it comes to emission-free mobility. BMW may be investing heavily in battery technology but the company has its BMW iX5 Hydrogen fuel cell car in testing albeit using Toyota fuel cells. Zipse said: One technology on its own will not be enough to enable climate-neutral mobility worldwide.

The science

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe but that does not mean it is easy to come by on Earth. Most pure hydrogen today is made by splitting carbon from methane, but that produces carbon emissions. Zero-emissions green hydrogen comes from electrolysis: using clean electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

To use hydrogen as a fuel it can be burned, or it can be used in a fuel cell: the hydrogen reacts with the oxygen from the air in the presence of a catalyst (often made from expensive platinum). That strips electrons that can run through an electric circuit, charging a battery that can power an electric motor.

Hydrogen offers refuelling in four minutes, higher payloads and longer range, according to Jean-Michel Billig, the chief technology officer for hydrogen fuel cell vehicle development at Stellantis. (The Mirai goes 400 miles on a fill-up.) Stellantis, which last month started production of hydrogen vans in France and Poland, is targeting businesses that want vehicles in constant use and do not want the downtime required for charging.

They need to be on the roads, Billig said. A taxi not running is losing money.

Many energy experts do not share the enthusiasm of the hydrogen carmakers

Stellantis thinks it can drive the sticker price down. Billig said that he expected by the end of this decade, hydrogen mobility or BEV will be equivalent from a cost perspective although the company will make both.

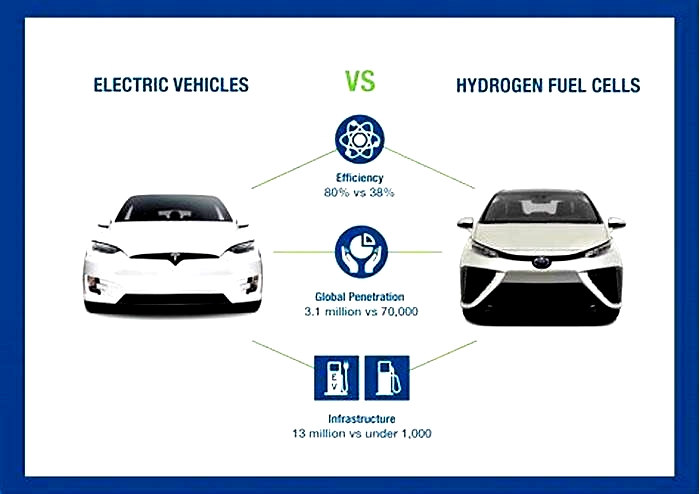

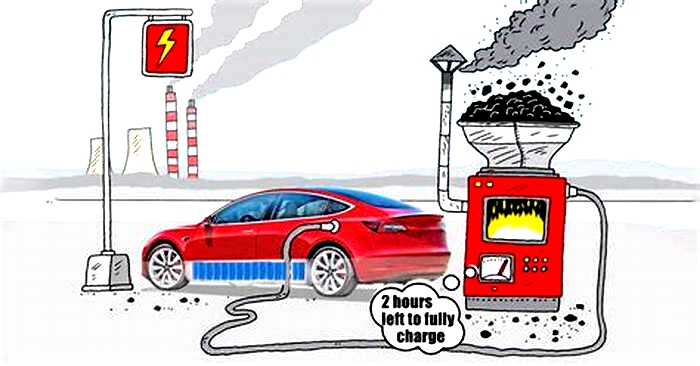

Many energy experts do not share the enthusiasm of the hydrogen carmakers. The Tesla boss Elon Musk describes the tech as fool sells: why use green electricity to make hydrogen when you can use that same electricity to power the car?

Every transformation of energy involves wasted heat. That means that hydrogen fuels inevitably deliver less energy to the vehicle. (Those losses increase much further if the hydrogen is burned directly or used to make e-fuels that can replace petrol or diesel in a noisy, hot internal combustion engine.)

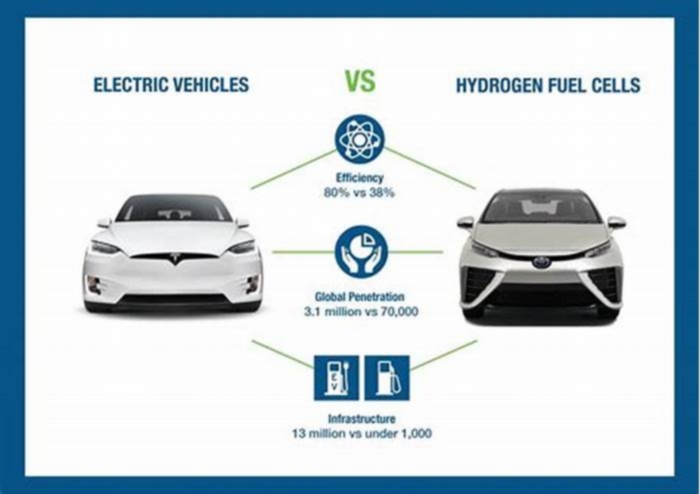

David Cebon, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Cambridge, said: If you use green hydrogen it takes about three times more electricity to make the hydrogen to power a car than it does just to charge a battery.

That could improve slightly but not enough to challenge batteries. Its difficult to do very much better, Cebon said.

Michael Liebreich, the chair of Liebreich Associates and the founder of the analyst firm Bloomberg New Energy Finance, created an influential hydrogen ladder a league table ranking hydrogen uses on whether there are cheaper, easier or more likely options. He placed hydrogen for cars in the row of doom, with very little chance of even a niche market.

Can hydrogen overtake batteries in cars? The answer is no, said Liebreich, without a moments hesitation. Carmakers betting on a large share for hydrogen are just wrong, and heading for an expensive disappointment, he added.

The key problem for hydrogen cars is not the fuel cell but actually getting the clean hydrogen where it is needed. The gas is highly flammable with all the safety concerns that entails must be stored under pressure and leaks easily. It also carries less energy per unit volume than fossil fuels, meaning it would require many times more tankers unless on-site electrolysers are used.

Investments are coming in hydrogen supplies, with heavy government subsidies in the US and Europe. But so far there has been a chicken-and-egg problem: buyers dont want hydrogen cars because they cant fill them, and there are no filling stations because there are no cars. Across Europe there are 178 hydrogen filling stations, half of which are in Germany, according to the European Hydrogen Observatory. Compare nine UK hydrogen stations with 8,300 petrol stations or 31,000 public charging locations (not counting plugs at homes).

Any caveats?

So why does the International Energy Agency think that hydrogen will account for 16% of road transport in 2050 in its pathway to net zero? The answer lies mostly with bigger vehicles such as buses and lorries.

Liebreich said he was convinced that batteries would still dominate energy supply for heavy goods vehicles to the point of co-founding a lorry charging company. There might be some hydrogen in HGVs but it will be the minority, he said.

Even Toyota acknowledges that hydrogen in cars has so far not been successful, mainly because of the lack of fuel supply, according to its technical chief, Hiroki Nakajima, speaking to Autocar in October. Lorries and long-distance buses offer a better hope for the technology, although it is also prototyping a hydrogen version of its Hilux pickup truck.

The verdict

The economics of hydrogen will change as governments enthusiasms wax or wane. Other things could change: technology could improve (within limits) and make the gas more attractive, and prospectors may be able to find cheaper white hydrogen drilled from the ground.

Yet for cars the die appears to be cast: batteries are already the post-petrol choice for almost every manufacturer. In the UK there have been fewer than 300 sales of hydrogen vehicles over 20 years, compared with 1m electric cars, according to the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders.

Batteries domination is likely to be extended as the money pouring into research and infrastructure addresses questions of range and charging times. Compared with that flood of investment, hydrogen is a trickle.

Hydrogens advocates now face the question of whether they can build profitable businesses in longer-distance, heavy-duty road transport. They need an answer soon on where they will source enough green, cheap hydrogen and whether the gas would be better used elsewhere.