Why hydrogen is not the future

For Many, Hydrogen Is the Fuel of the Future. New Research Raises Doubts.

It is seen by many as the clean energy of the future. Billions of dollars from the bipartisan infrastructure bill have been teed up to fund it.

But a new peer-reviewed study on the climate effects of hydrogen, the most abundant substance in the universe, casts doubt on its role in tackling the greenhouse gas emissions that are the driver of catastrophic global warming.

The main stumbling block: Most hydrogen used today is extracted from natural gas in a process that requires a lot of energy and emits vast amounts of carbon dioxide. Producing natural gas also releases methane, a particularly potent greenhouse gas.

And while the natural gas industry has proposed capturing that carbon dioxide creating what it promotes as emissions-free, blue hydrogen even that fuel still emits more across its entire supply chain than simply burning natural gas, according to the paper, published Thursday in the Energy Science & Engineering journal by researchers from Cornell and Stanford Universities.

To call it a zero-emissions fuel is totally wrong, said Robert W. Howarth, a biogeochemist and ecosystem scientist at Cornell and the studys lead author. What we found is that its not even a low-emissions fuel, either.

To arrive at their conclusion, Dr. Howarth and Mark Z. Jacobson, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford and director of its Atmosphere/Energy program, examined the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of blue hydrogen. They accounted for both carbon dioxide emissions and the methane that leaks from wells and other equipment during natural gas production.

The researchers assumed that 3.5 percent of the gas drilled from the ground leaks into the atmosphere, an assumption that draws on mounting research that has found that drilling for natural gas emits far more methane than previously known.

They also took into account the natural gas required to power the carbon capture technology. In all, they found that the greenhouse gas footprint of blue hydrogen was more than 20 percent greater than burning natural gas or coal for heat.(Running the analysis at a far lower gas leak rate of 1.54 percent only reduced emissions slightly, and emissions from blue hydrogen still remained higher than from simply burning natural gas.)

Such findings could alter the calculus for hydrogen. Over the past few years, the natural gas industry has begun heavily promoting hydrogen as a reliable, next-generation fuel to be used to power cars, heat homes and burn in power plants.

In the United States, Europe and elsewhere, the industry has also pointed to hydrogen as justification for continuing to build gas infrastructure like pipelines, saying that pipes that carry natural gas could in the future carry a cleaner blend of natural gas and hydrogen.

While many experts agree that hydrogen could eventually play a role in energy storage or powering certain types of transportation such as aircraft or long-haul trucks, where switching to battery-electric power may be challenging there is an emerging consensus that a wider hydrogen economy that relies on natural gas could be damaging to the climate. (At current costs, it would also be very expensive.)

The latest study added to the evidence, said Drew Shindell, a professor of earth science at Duke University. Dr. Shindell was the lead author of a United Nations report published this year that found that slashing emissions of methane, the main component of natural gas, is far more vital in tackling global warming than previously thought. In a new report published this week, the U.N. warned that essentially all of the rise in global average temperatures since the 19th century has been driven by the burning of fossil fuels.

The hydrogen study showed that the potential to keep using fossil fuels with something extra added on as a potential climate solution is neither fully accounting for emissions, nor making realistic assumptions about future costs, he said in an email.

The Hydrogen Council, an industry group founded in 2017 that includes BP, Shell, and other big oil and gas companies, did not provide immediate comment. A McKinsey & Company report co-authored with industry estimated that the hydrogen economy could generate $140 billion in annual revenue by 2030 and support 700,000 jobs. The study also projected that hydrogen could meet 14 percent of total American energy demand by 2050. BP declined to comment.

In Washington, the latest bipartisan infrastructure package devotes $8 billion to creating regional hydrogen hubs, a provision originally introduced as part of a separate bill by Senator Joe Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia, a major natural gas producing region. Among companies that lobbied for investment in hydrogen were NextEra Energy, which has proposed a solar-powered hydrogen pilot plant in Florida.

Some other Democrats, like Representative Jamie Raskin of Maryland, have pushed back against the idea, calling it an empty promise. Environmental groups have also criticized the spending. Its not a climate action, said Jim Walsh, a senior energy policy analyst at Food & Water Watch, a Washington-based nonprofit group. Its this is a fossil fuel subsidy with Congress acting like theyre doing something on climate, while propping up the next chapter of the fossil fuel industry.

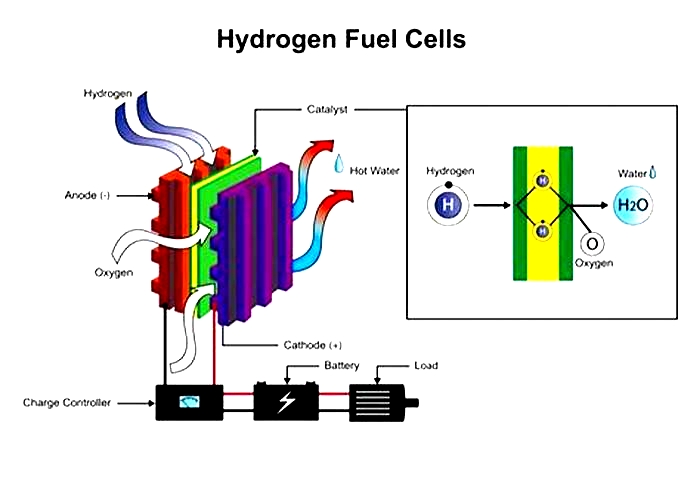

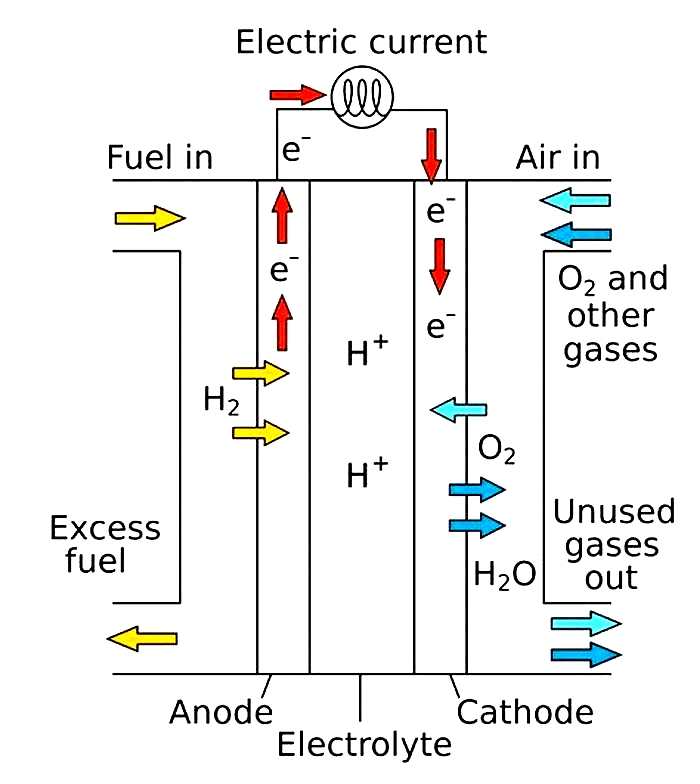

Jack Brouwer, director of the National Fuel Cell Research Center at the University of California, Irvine, said that hydrogen would ultimately need to be made using renewable energy to produce what the industry calls green hydrogen, which uses renewable energy to split water into its constituent parts, hydrogen and oxygen. That, he said, would eliminate the fossil and the methane leaks.

Hydrogen made from fossil fuels could still act as a transition fuel but would ultimately be a small contributor to the overall sustainable hydrogen economy, he said. First we use blue, then we make it all green, he said.

Today, very little hydrogen is green, because the process involved electrolyzing water to separate hydrogen atoms from oxygen is hugely energy intensive. In most places, there simply isnt enough renewable energy to produce vast amounts of green hydrogen. (Although if the world does start to produce excess renewable energy, converting it to hydrogen would be one way to store it.)

For the foreseeable future, most hydrogen fuel will very likely be made from natural gas through an energy-intensive and polluting method called the steam reforming process, which uses steam, high heat and pressure to break down the methane into hydrogen and carbon monoxide.

Blue hydrogen uses the same process but applies carbon capture and storage technology, which involves capturing carbon dioxide before it is released into the atmosphere and then pumping it underground in an effort to lock it away. But that still doesnt account for the natural gas that generates the hydrogen, powers the steam reforming process and runs the CO2 capture. Those are substantial, Dr. Howarth of Cornell said.

Amy Townsend-Small, an associate professor in environmental science at the University of Cincinnati and an expert on methane emissions, said more scientists were starting to examine some of the industry claims around hydrogen, in the same way they had scrutinized the climate effects of natural gas production. I think this research is going drive the conversation forward, she said.

Plans to produce and use hydrogen are moving ahead. National Grid, together with Stony Brook University and New York State,is studying integrating hydrogen into its existing gas infrastructure, though the project seeks to produce hydrogen using renewable energy.

Entergy believed hydrogen was part of creating a long-term carbon-free future, complementing renewables like wind or solar, which generate power only intermittently, said Jerry Nappi, a spokesman for the utility. Hydrogen is an important technology that will allow utilities to adopt much greater levels of renewables, he said.

National Grid referred to its net zero plan, which says hydrogen will play a major role in the next few decades and that producing hydrogen from renewable energy was the linchpin.

New York State was exploring all technologies including hydrogen in support of its climate goals, said Kate T. Muller, a spokeswoman for the states Energy Research and Development Authority. Still, its researchers would review and consider the blue hydrogen paper, she said.

Sustainability and Climate Change: Join the Discussion

Our Netting Zero series of virtual events brings together New York Times journalists with opinion leaders and experts to understand the challenges posed by global warming and to take the lead for change.

Why is hydrogen no longer the fuel of the future?

6 mins read26 January 2022

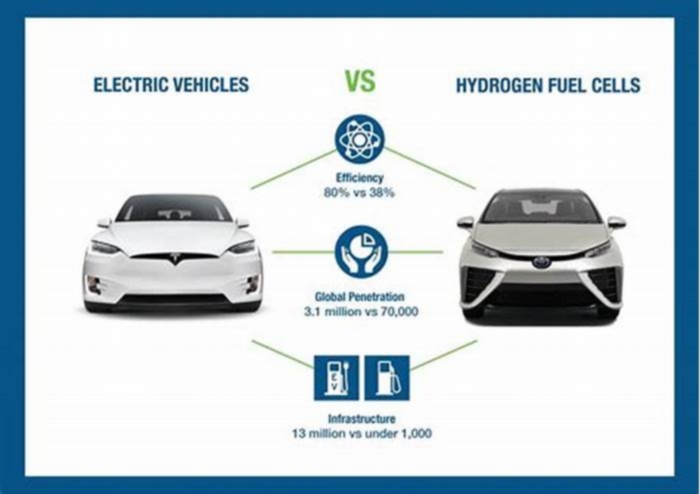

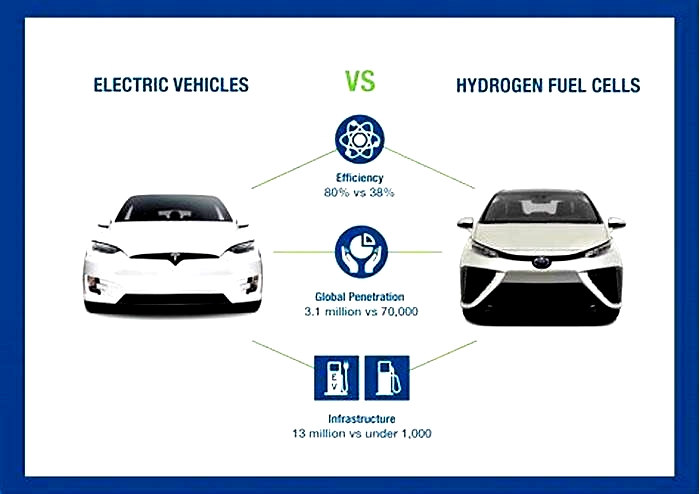

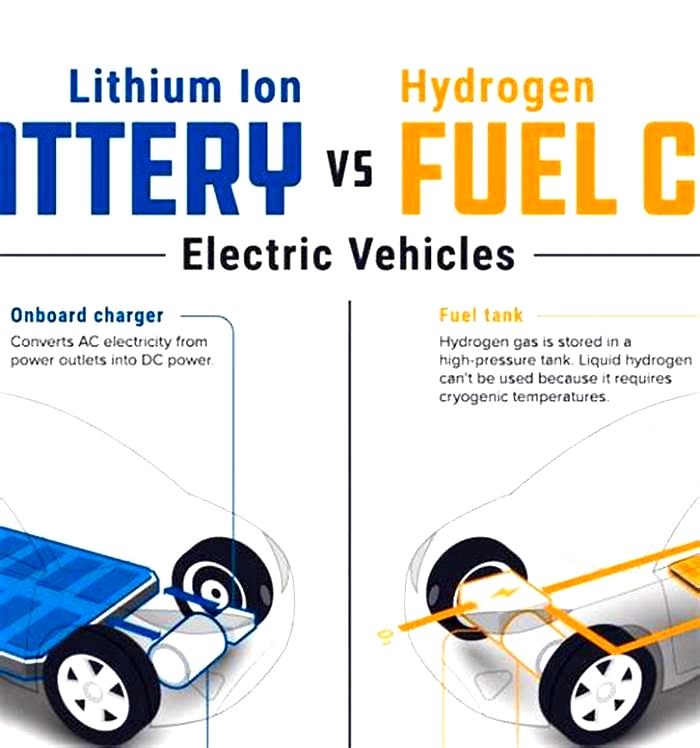

Hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) should be making their big stage entrance right about now. Petrol and diesel cars are under fire as the UK government pushes harder for zero emissions ahead of its ban on new ICE vehicles from 2030.

Meanwhile, hydrogen is a key part of emissions reduction from British power generation (plans were announced last year to produce 5GW worth annually by 2030 roughly the output of two nuclear plants).

To access this content please subscribe

Already registered?

Login 20% annual savingRegular membership

Automatic renewal

Team membership

799

Price includes a 20% discount for a team of 5

Green hydrogen: Fuel of the future has big potential but a worrying blind spot, scientists warn

If hydrogen leaks into the atmosphere, the benefits of using it over fossil fuels could be completely wiped out, scientists warn.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTMade exclusively with renewable power, green hydrogen is emerging as a promising alternative to polluting fossil fuels.But thismuch-touted fuel of the future may have a pitfall.

Some scientists say the lack of data on leaks and the potential harm they could cause is a blind spot for the nascent industry.

At least four studies published this year say hydrogen loses its environmental edge when it seeps into the atmosphere. This is because it reduces the concentration of molecules that destroy the greenhouse gases already there, potentially contributing to global warming.

If even 10 per cent leaks during its production, transportation, storage or use, the benefits of using green hydrogen over fossil fuels would be completely wiped out, twoscientists told Reuters.

They say the lack of technology for monitoring hydrogen leaks means there is a data gap, and more research is needed to calculate its net impact on global warming before final investment decisions are taken.

Yet governments and energy companies are lining up big bets on green hydrogen.

In Europe, the energy squeeze prompted by Russia's invasion of Ukraine is forcing governments to seek alternative sources of power - and the spike in gas prices has made green hydrogen appear much more affordable.

The European Union approved 5.2 billion in subsidies for green hydrogen projects in September.The United States, meanwhile, included billions of dollars of green hydrogen tax credits in its Inflation Reduction Act.

Are we ready to transition to green hydrogen?

Studieson the risk of leaks undermining green hydrogen's climate benefitshave been published by Columbia University, the Environmental Defense Fund, the universities of Cambridge and Reading, and the Frazer-Nash Consultancy.

"We need much better data. We need much better devices to measure the leakage, and we need regulation which actually enforces the measurement of the leakage," says Anne-Sophie Corbeau, a researcher at Columbia University's Center on Global Energy Policy.

It estimates that leakage rates could reach up to 5.6 per cent by 2050 when hydrogen is being used more widely.

Norway's climate research institute CICERO is also working on a three-and-a-half-year study, due to conclude in June 2024, on the impact of hydrogen emissions. Maria Sand, who is leading the research, says there is a big gap in the science.

"We need to be aware of the leakages, we need some answers... There is big potential for hydrogen, we just need to know more before we make the big transition."

How common are hydrogen leaks?

Hydrogen has not been monitored for leaks in the past, and most of the odourless gas used now is made where it is consumed - but there are plans to pipe and ship it vast distances.

The fossil fuel industry hopes that hydrogen could eventually move through existing infrastructure, such as gas pipelines and liquefied natural gas import and export terminals.

About 1 per cent of the natural gas - which is mostly methane - moving through European infrastructure leaks. However, rates are higher in some countries including Russia, according to analysts and satellite images of leaks.

"There's a lot we don't know about hydrogen," says Sand. "We don't know yet if we can assume it will behave the same way as methane."

Initial results of tests in pipelines at DNV's Spadeadam research site in northern England showed that hydrogen leaks in the same places and rates as natural gas.Companies working on green hydrogen projects say, however, that careful monitoring would be needed.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTScientists and analysts say that as hydrogen molecules are much smaller and lighter than those in methane, they are harder to contain.

Once hydrogen enters pipelines, it can weaken metal pipes which can lead to cracking. Hydrogen is also far more explosive than natural gas which could create safety issues.

While potential leakages of hydrogen are not expected to be on a scale that could derail all green hydrogen plans, any seepage would erode its climate benefits, scientists say.

Green hydrogen vs grey hydrogen

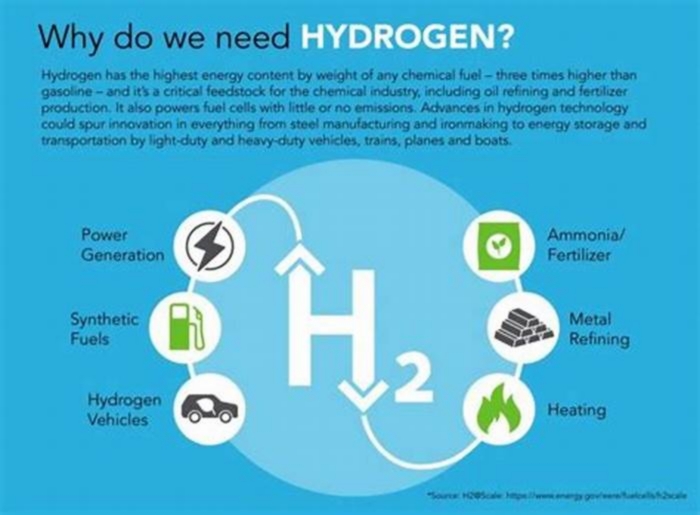

Hydrogen, a highly combustible gas that can store and deliver energy, is the simplest and most abundant element on Earth, but it doesn't typically exist in its free form and must be extracted from compounds that contain it, such as water, coal, natural gas or biomass.

Producing the hydrogen long used in oil refineries, chemicals factories and the fertiliser industry relies on natural gas or coal,in processes that emit large amounts of carbon dioxide. This type of fossil-based hydrogen is often referred to as 'grey' hydrogen.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTIndustry experts estimate that close to 95 per cent of hydrogen production currently uses fossil fuels, and it generates as much CO2 as the emissions of the UK and Indonesia combined.

'Green' hydrogen, by contrast, is made by using renewable energy to split waterinto its two components - water and oxygen -through electrolysis, without producing greenhouse gases.

This type of 'clean' hydrogen could replace fossil fuel in sectors that cant easily switch to electricity, such as steel making or heavy transport.

The chief attraction of using hydrogen as a fuel is that the main by-product is water vapour, along with small amounts of nitrogen oxides, making it far less polluting than fossil fuels - assuming it doesn't seep out.

Leaks are one of many issues plaguing the adoption of green hydrogen, besides high costs, safety concerns, and the need to invest in enough renewable energy to make it, as well as in the infrastructure to store and transport the colourless gas.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTHow can the risks of hydrogen leaks be assessed?

In December 2022, Brussels called for applications for funding for more research into the risks linked to a large-scale deployment of hydrogen. It asked the research to show how hydrogen could reduce global warming by replacing fossil fuels, but also how it could contribute to global warming in the event of leakages.

The Environmental Defense Fund's study, meanwhile, urged governments and businesses to gather data on hydrogen leakage rates first, then identify where the risks were highest and how to mitigate them before building the infrastructure needed.

The Frazer-Nash report also flagged how measures to prevent hydrogen leaks needed to be taken into account to allow for greater up-front and maintenance costs.

"The more we know about how to produce it in a sustainable way, and the regulation and management needed, the more it costs and therefore that limits its use unless there is no alternative," says Richard Lowes, senior associate at The Regulatory Assistance Project think-tank.

Hydrogen projects are on the rise globally

Almost 300 green hydrogen projects are under construction or have started up worldwide, but the vast majority are tiny demonstration plants, International Energy Agency data shows.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTThe largest is in China where Ningxia Baofeng Energy Group is using green hydrogen produced from solar power to make petrochemicals such as polyethylene and polypropylene.

Consultancy DNV forecasts that green hydrogen would need to meet about 12 per cent of the world's energy demand by 2050 to hit Paris climate targets. Based on the current pace of development and DNV's modelling of future uptake, the world is only on track to reach about 4 per cent, DNV says.

David Cebon, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Cambridge, says 4 per cent might be only what's "manageable", given the huge amount of renewable energy needed to make enough green hydrogen.

To replace the dirty hydrogen used now in refineries, fertiliser and chemical plants, almost double the electricity produced by every wind turbine and solar panel worldwide would be required - and that's before green hydrogen is used for anything else, such as steelmaking, transport or heating, Cebon says.

Still, the EU is considering mandates for green hydrogen's use in transport, while countries such as South Korea, Japan and China have targets for hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTEnergy giant BP, which is planning to build multiple green hydrogen projects, including a facility in Britain due to start in 2025 known as HyGreen Teesside, says it is developing leakage monitoring systems.

"We really want to launch an effort now to assess how low can we maintain the level of leakage across a value chain and that's going to be the critical thing," says Felipe Arbelaez, senior vice president for hydrogen and carbon capture at BP.