Will electric cars get cheaper in 5 years

3 reasons why electric cars will soon get a lot cheaper

- Some automakers are slowing down EV production, saying electric vehicles are too expensive.

- They have a point, with drivers looking to buy an EV having to pay a hefty premium.

- But new batteries, production methods, and improved charging networks mean prices are set to drop.

Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you're on the go.

EVs have an affordability problem.

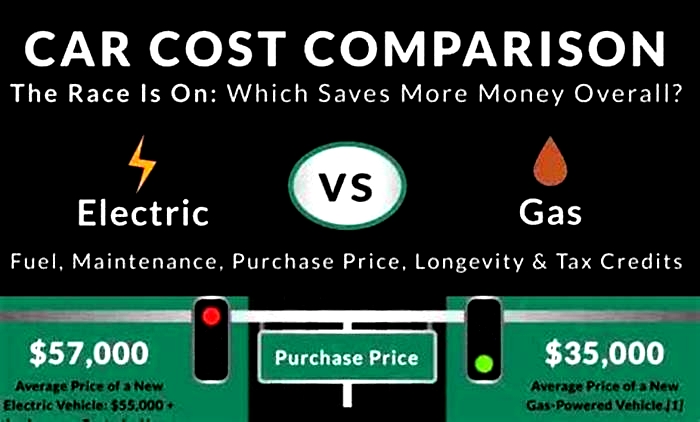

There just aren't very many cheap options with the average price hovering just over $50,00 in September, according to Kelley Blue Book data.

Auto execs have pointed to high prices as a big reason why demand for electric cars has slumped this year.

Several have slowed down their EV plans as a result, with Ford postponing a $12 billion investment and General Motors abandoning plans to build 500,000 EVs by the first half of 2024.

All this, however, may be about to change soon. EV sales are on the rise, with more than 1 million electric vehicles expected to be sold in the US this year, taking a record 9% of the passenger car market, according to Atlas Public Policy.

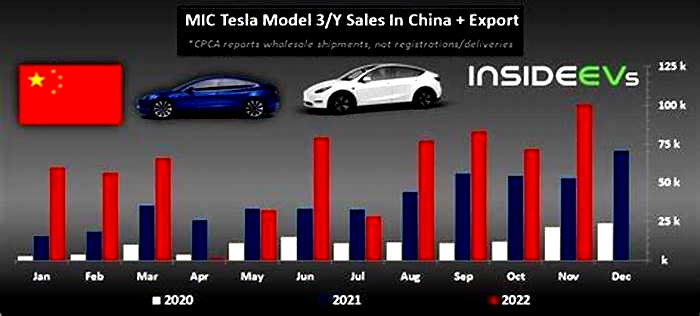

That share is still well behind other countries, with EVs reaching 33% of sales in China and 35% in Germany in the first three months of 2023, according to Bloomberg data.

Tesla is reportedly planning to put a 25,000 euro ($27,000) car into production next year, and a number of fast-moving developments in the technology behind electric vehicles may soon see prices plummet.

Goldman Sachs even thinks EVs will hit price parity with gas-powered cars by the middle of this decade.

Here's three reasons why electric cars are getting more affordable.

1. Cheaper battery packs

By far the most expensive part of any EV is the battery, and spiking battery prices have hit automakers hard.

However, the long-term trend is still heading towards cheaper battery packs.

Prices may have risen in 2022, but the Department of Energy estimates that the price of a lithium-ion battery pack dropped by 89% between 2008 and 2022, and Goldman Sachs says that prices for batteries will fall a further 40% by 2025.

"The battery is the single biggest cost going into electric vehicles and it's subject to the same kind of technology price curves that you see elsewhere," David Browne, the UK chief of EV manufacturer Smart, told Business Insider.

Leading the charge is the development of new classes of EV batteries, including sodium-ion batteries, which are more sustainable and cost-effective than power cells based on lithium. And, solid-state batteries, which are lighter and have more range.

In October, Toyota announced a breakthrough in solid-state technology that it said would allow it to halve the weight of its batteries by the late 2020s. Manufacturers think there are more breakthroughs to be made.

"We're only scratching the surface in battery development," said Browne.

"Working with ICE engines, you were chasing the smallest improvement in efficiency because people had been working on it for over a hundred years," he said.

"But battery technology is moving so quickly, and there are so many exciting developments, that there is lots we can do to improve efficiency," he added.

2. More charging points

Another speed bump in the road to mass EV adoption is the US's charging network, which is still patchy even in big cities such as Los Angeles.

Matthias Preindl, a professor of electrical engineering at Columbia University, told BI that boosting charging networks would allow manufacturers to put less emphasis on powerful range-boosting batteries, making their vehicles lighter and cheaper to produce and in turn, meaning lower prices for the consumer.

Tesla's North American Charging Standard and the CSS network are the two major charging networks operating in the US.

Tesla's network is expanding rapidly, with the company planning to double the number of chargers it offers by 2024. It is also becoming the industry standard, with both Ford and GM announcing that their EVs will use Tesla superchargers from 2024 something Cox Automotive director Stephanie Valdez Streaty believes will help boost the US' charging infrastructure.

"From an adoption standpoint, a consumer really wants to have that same experience as they do with an ICE (internal combustion engine vehicle), where it's never a barrier," she told BI.

"I think the key thing when it comes to charging infrastructure is going to be standardization," she said.

3. Economies of scale

One key headache for automotive companies is that the best way to bring down the cost of making EVs is to produce more of them.

"You have to get to a certain scale to really start to make money on electric cars and for the costs to go down," Valdez Streaty said.

"You begin to see more innovation and improved efficiencies in the manufacturing process," she added.

That's an issue for legacy automakers, who have increasingly moved to cut EV production targets in the face of slowing demand.

Some companies such as Tesla are bringing down costs by changing how they mass produce their cars, with Elon Musk's firm pioneering a new process called "gigacasting" that allows it to produce large parts of a car's body through molten metal poured into high-pressure molds.

Other firms like Toyota are racing to adopt similar methods, which allow manufacturing plants to produce cars that are both lighter and cheaper.

However, there are concerns that the new method could make it harder to replace car parts, and Browne said that while Tesla's tactics are good for keeping costs down, they could lead to a spike in repair costs.

"The trade-off is if you've got one big mega casting down the side of the car and somebody damages that, you've then got an issue with repair costs," he said.

Alongside new production techniques, major automakers are still expanding their EV assembly lines, even if they aren't doing it quite as quickly and that is good news for EV prices.

"I think one of the challenges that we're seeing is that we're still ramping up EV production. So as production increases we will see prices also decreasing long-term," said Preindl.

Electric cars will be cheaper to produce than fossil fuel vehicles by 2027

Electric cars and vans will be cheaper to produce than conventional, fossil fuel-powered vehicles by 2027, and tighter emissions regulations could put them in pole position to dominate all new car sales by the middle of the next decade, research has found.

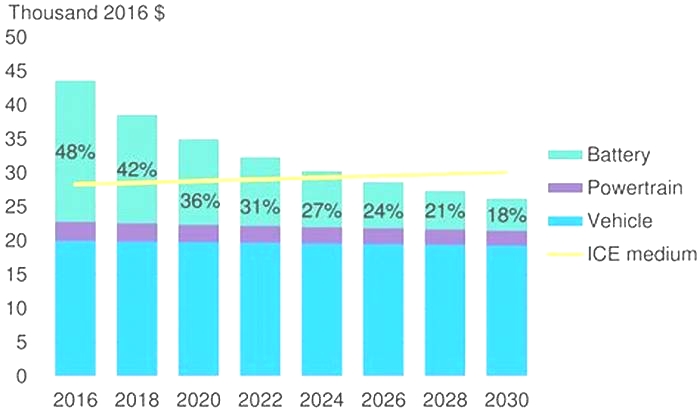

By 2026, larger vehicles such as electric sedans and SUVs will be as cheap to produce as petrol and diesel models, according to forecasts from BloombergNEF, with small cars reaching the threshold the following year.

Electric vehicles reaching price parity with the internal combustion engine is seen as a key milestone in the worlds transition from burning fossil fuels.

The falling cost of producing batteries for electric vehicles, combined with dedicated production lines in carmarkers plants, will make them cheaper to buy, on average, within the next six years than conventional cars, even before any government subsidies, BloombergNEF found.

The current average pre-tax retail price of a medium-sized electric car is 33,300 (28,914), compared with 18,600 for a petrol car, according to the research. In 2026, both are forecast to cost about 19,000.

By 2030, the same electric car is forecast to cost 16,300 before tax, while the petrol car would cost 19,900.

The reports timeline for cost parity is more conservative than other forecasts, including one from the investment bank UBS, which has predicted that electric cars will cost the same to make by 2024.

However, forecasters are in agreement that the cost of new batteries will continue to fall in the coming years.

The new study, commissioned by Transport & Environment, a Brussels-based non-profit organisation that campaigns for cleaner transport in Europe, predicts new battery prices will fall by 58% between 2020 and 2030 to $58 per kilowatt hour.

A reduction in battery costs to below $100 per kWh, is viewed as an important step towards greater take-up of fully electric vehicles, and would largely remove the financial appeal of hybrid electric vehicles, which combine a battery with a conventional engine.

Electric vehicle sales boomed in 2020, especially in the EU and China, but environmental campaigners are calling on governments to introduce tougher emissions regulations to encourage more consumers to make the switch.

The UK government plans to ban the sale of new fossil fuel vehicles from 2030, while European companies have called on the EU to set 2035 as the end date for selling new combustion engine vehicles in the bloc.

Julia Poliscanova, T&Es senior director for vehicles and emobility, said stricter CO2 targets were needed to accelerate the switch to electric.

With the right policies, battery electric cars and vans can reach 100% of sales by 2035 in western, southern and even eastern Europe. The EU can set an end date in 2035 in the certainty that the market is ready. New polluting vehicles shouldnt be sold for any longer than necessary, she said.

The high cost of batteries, accounting for between a quarter and two-fifths of the cost of an electric vehicle, has previously led to reluctance among the worlds biggest carmakers to switch production away from their profitable fossil fuel models.

Sign up to the daily Business Today email or follow Guardian Business on Twitter at @BusinessDesk

Reduced cost is seen as critical to make electric vehicles more attractive to consumers, especially when combined with increased range the distance a vehicle can travel before it requires charging, and an improved charging network.

Once you are well over 200 miles per range, and youve got a really good charging infrastructure, it becomes a no-brainer. Weve seen that in Norway, said David Bailey, a professor of business economics at the University of Birmingham.

However, he believes the UK government needs to improve the charging network: We are lagging behind some other north European nations, and we certainly need a much more rapid rollout of the charging infrastructure, at home, on-street and fast.

Falling Lithium Prices Are Making Electric Cars More Affordable

Lithium, the common ingredient in almost all electric-car batteries, has become so precious that it is often called white gold. But something surprising has happened recently: The metals price has fallen, helping to make electric vehicles more affordable.

Since January, the price of lithium has dropped nearly 20 percent, according to Benchmark Minerals, even as sales of electric vehicles have soared. Cobalt, another important battery material, has fallen by more than half. Copper, essential to electric motors and batteries, has slipped about 18 percent, even though U.S. mines and copper-rich countries like Peru are struggling to increase production.

The sharp moves have confounded many analysts who predicted that prices would stay high, or even climb, slowing the transition to cleaner forms of transportation, an essential component of efforts to limit climate change.

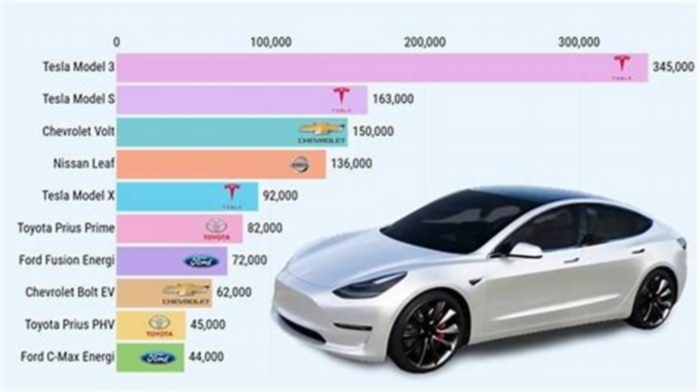

Instead, the drop in commodity prices has made it easier for carmakers to cut prices for electric vehicles. This month, Tesla lowered the prices of its two most expensive cars, the Model S sedan and Model X sport utility vehicle, by thousands of dollars.

That followed cuts in January by Tesla to its more affordable Model 3 and Model Y, and by Ford Motor to its Mustang Mach-E. The average price of an electric vehicle in the United States fell $1,000 in February compared with January, according to Kelley Blue Book.

For electric vehicles, the major roadblock is cost, said Kang Sun, the chief executive of Amprius Technologies, a young battery maker that this month announced plans for a factory in Colorado. The falling price of lithium, he said, is going to promote E.V. sales.

Dr. Sun thinks prices could fall much further because demand for the metal has not risen as fast as some in the industry expected.

As with any commodity, there is a wide range of opinion on what has caused the recent drop in prices and on how much lithium will cost in the coming months and years.

Some analysts said the falling price of lithium was caused by short-term factors like slowing sales growth in Europe and China after subsidies for electric car purchases expired. But other industry experts said the drop suggested that new mines and processing plants were solving the lithium problem sooner than many analysts had thought was possible.

Even after falling so much, lithium prices remain so high that mining and processing the metal is an unusually profitable business. The metal, uniquely suited for batteries because of its ability to store energy, costs about $5,000 to $8,000 per ton to produce. It sells for 10 times that amount, according to Mobility Impact Partners, a New York private equity firm that invests in the electric vehicle industry, among other areas.

Given those fat profit margins, investors and banks are eager to invest in, or lend to, mining and processing projects. The federal government is awarding grants worth tens of millions of dollars to lithium prospectors and processors.

You cant have profit margins that are 10 times what it costs to extract, said Shweta Natarajan, a partner at Mobility Impact Partners who has analyzed the lithium market. You will see that come down.

Financing is very easy to come by, Ms. Natarajan added. There is no reason to think you wouldnt have new projects opening up to meet any shortages.

But others, including members of the Biden administration, are less confident. The supply of lithium has to increase 42-fold by 2050 to support a transition to clean energy, said Jose W. Fernandez, the under secretary for economic growth, energy and the environment at the State Department.

We have to find additional sources of supply because 42 times is a lot, Mr. Fernandez said in an interview. Right now, we dont have enough.

There is plenty of lithium in the world. But it was not considered very valuable until sales of electric vehicles began to take off in the last few years. As demand soared, the industry rushed to start new mines, and refineries increased their capacity to process the ore.

The mining is not what is driving the costs, said Bold Baatar, the chief executive of the copper production unit at the mining giant Rio Tinto. Its the availability of processing facilities.

Most lithium refineries are in China, and few managers and engineers outside that country know how to build processing plants. Beijings near-monopoly on an essential resource alarmed the Biden administration, which has allocated billions of dollars to encourage companies to develop lithium mines and refineries in the United States or in countries with which it shares close political and economic ties.

Supplies of lithium and other critical materials are a national security issue, Mr. Fernandez said. Last year, the administration established the Minerals Security Partnership, he said, a group that includes the European Union and 12 industrialized nations, including Australia, Japan and Britain, to locate mining opportunities and financing, and to promote recycling.

The Department of Energy is doling out $3 billion in grants to create a domestic battery supply chain. In addition, the Inflation Reduction Act, which Mr. Biden signed into law last year, provides tax credits for battery production.

American Battery Technology was awarded a grant by the Energy Department to help it build a lithium refinery and a battery-recycling facility in Nevada. The company is also developing a lithium mine in the state.

Ryan Melsert, the chief executive of American Battery Technology, attributed the recent decline in lithium prices to temporary factors like a seasonal slowdown in electric vehicle sales in China. We expect to see very high prices for the foreseeable future, Mr. Melsert said.

Vivek Chidambaram, the senior managing director for strategy at Accenture, the consulting firm, also expects the decline to be ephemeral. Lithium prices have fallen because sales of electric vehicles, while still brisk, are not growing as fast as automakers expected, he said. That has led suppliers to produce more than is needed.

There was a time when people believed electric vehicles would grow very rapidly, Mr. Chidambaram said. Then the reality of how fast they were actually growing caught up. He expects lithium prices to fluctuate for the next several years.

Automakers, fearful of lithium shortages and rising prices, have taken steps to ensure a steady supply. They have signed contracts with lithium suppliers that require them to buy certain quantities of the metal. In some cases, carmakers are getting into the lithium business more directly. Tesla said this month that it would build a lithium processing plant near Corpus Christi, Texas.

General Motors said in January that it would invest $650 million in Lithium Americas, which is developing a mine in Nevada known as Thacker Pass. The deal makes G.M. the largest customer and shareholder of Lithium Americas.

Those investments could turn out to be money losers if the price of lithium continued to fall, analysts have warned.

There is also a risk that improvements in battery technology could affect demand for lithium in unexpected ways.

Solid-state batteries being developed by several companies would require even more lithium than batteries in use today, increasing demand. But those batteries probably wont appear in mass-produced vehicles for several years. Other advances in production techniques and chemistry would allow batteries to be smaller and lighter without sacrificing performance, reducing the need for lithium.

Shifting technology has already hit cobalt. The price of that metal plunged in part because of the increasing popularity of batteries made without cobalt from lithium, iron and phosphate, a combination known as L.F.P. Stockpiling by a major cobalt supplier may also have hit prices, analysts say.

L.F.P. batteries are heavier than batteries made with cobalt, but they are significantly less expensive and last longer. And L.F.P. batteries dont come with the taint associated with cobalt, most of which comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where mining operations are known for child labor and abysmal working conditions.

Ford said in February that it would spend $3.5 billion to build a plant in Michigan to produce L.F.P. batteries using technology from Contemporary Amperex Technology, or CATL, a Chinese company that is the world's largest battery manufacturer.

No technology on the horizon would eliminate lithium from mass-produced car batteries. For that reason, few analysts are predicting that the price of lithium will fall as low as it did in 2020, when it dropped below $10 per kilogram.

Even when the price comes down from its elevated levels, Ms. Natarajan, of Mobility Impact Partners, said, there still is a very healthy profit margin.