Will electric cars take over in the future

The future of electric cars: When will electric cars take over in Australia?

If youre actually one of the few people still wondering Are electric cars the future?, weve got news for you - EVs have already snuck up on us, all ninja-like, with their silent engines and zero-emission tailpipes, to usher in a new age of motoring where petrol is just a dirty word (although not as dirty as diesel, which is also going the way of the horse-drawn carriage).

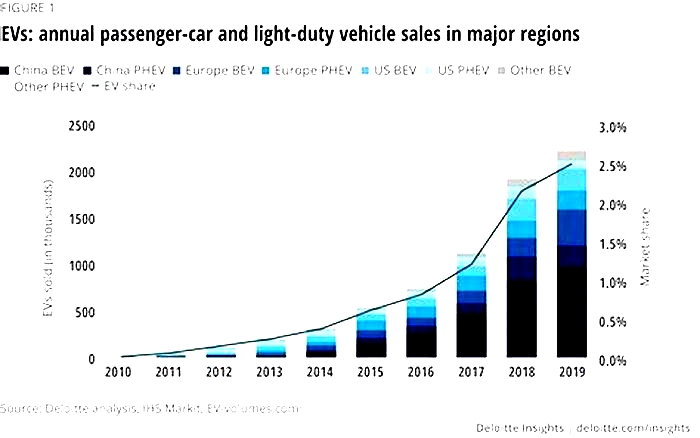

According to ResearchAndMarkets.com's recent Electric Vehicle Outlook: 2021 and Beyond report, EVs will represent 48 per cent of all new cars sold globally in 2030 - significantly up from the 7 per cent thats forecast for 2021. That is, even by Elon Musks standards, an enormous jump.

To put it into perspective unit-wise, BloombergNEF is predicting global sales of EVs will leap from 3.1 million units in 2020 to 14 million in 2025, accounting for around 16 per cent of all passenger-vehicle sales.

Read more about electric cars

The rapid acceleration toward an electric cars future is being driven by a number of key factors, chief among them the decision by 14 countries to set a date to phase out the production of internal-combustion-engine vehicles that rely on fossil fuels, including 2030 in the UK (although hybrids will be allowed until 2035), 2030 in Germany and 2025 in Norway, where more than 70 per cent of new car sales in 2020 were electric.

The phasing out of ICE vehicles has seen major car companies also setting targets to go fully electric, including Jaguar Land Rover (2025), Volvo (2030), Mazda (2030), Ford in Europe (2030), Nissan (early 2030s), GM (2035), Daimler (2039), and Honda (2040).

China has pledged to become carbon neutral by 2060, and plans to ensure only 'new-energy' vehicles are sold by 2035, as one of the world's largest markets, that's a huge number of electric or hydrogen vehicles which will need to be built. To put it in perspective, China's electrified vehicle market nearly tripled over the course of 2021, with 3.4 million vehicles sold.

Download the EVGuide Report, 2022

Australia's one-stop snapshot of all things relating to electric cars.

Download for freeIn Germany - a country with a massive automotive industry, and home to iconic brands like Audi, BMW and Mercedes-Benz - EV sales are expected to take up a huge 40 per cent of sales by 2025.

One of the main reasons for the growing popularity of EVs in China is their affordability: the Wuling Hongguang Mini EV from SAIC-GM-Wuling, which is being marketed as the Peoples Commuting Tool, is priced at 32,800 yuan, which translates to just under$7000, and the low price has helped it to become the worlds second highest-selling EV behind the Tesla Model 3, with the brand moving 395,451 units in the last year alone.

Tax breaks and other incentives in countries like the UK and Norway are also helping to push EV sales up, but the lack of similar schemes in Australia is one big reason why EV sales here in 2021made up a relativelydismal 1.6per cent of new-car sales.

While the Federal Governments efforts have so far been lacking - or non-existent - the states and territories have been picking up the slack with their own incentives. The NSW Government is arguably leading the charge with an Electric Vehicle Strategy offering $500m of investment to encourage EV uptake.

The NSW Government has also set a goal of 52 per cent of all new-car sales being electric vehicles by 2030-31; Victoria has set a similar goal of 50 per cent by 2030, In Queensland, the target is every new car to be electric by 2036, and other states are yet to lock in specific targets.

Although car manufacturers are hardly clamouring to release new EV models in Australia, due to the current market stagnation, that doesnt mean the future of electric cars in Australia is bleak. Its expected that 58 EV models will be available here by the end of 2022, compared to the 31 available in 2021.

Its difficult to predict when will electric cars will take over completely, its safe to say that in the not-too-distant future, electric cars will undoubtedly be ruling the roads on a global scale.

Notable upcoming EVs:

Here are our list of five incoming EVs which should make a significant impact on the number of zero emissions vehiclessold in Australia.

Tesla Model Y

Timing: 2022

The Model Y is essentially an SUV version of the most popular electric car in Australia, the Model 3, and it shot to the top of the charts in its home market of America as by far its best-selling zero emissions vehicle in 2021.We don't doubt many potential EV buyers are waiting for their opportunity to buy one of these, with Tesla expected to launch it in Australia before the end of 2022.

BYD Atto 3

Timing: August2022

BYD sells massive numbers of electric vehicles in China, rivalling Volkswagen Group and Tesla, and the Atto 3 is the brand's first mass-market offering in Australia. It aims to offer something which no brand has really managed thus far, a competitively-priced smallSUV with a long range. With prices starting from $44,381 before on-roads for the base model which offers 320km of WLTP-certified range, we have no doubt that it will make an impact like the MG ZS EV before it.

Volkswagen ID.4

Timing: 2023 (est.)

Volkswagen has been slow to the EV party in Australia, citing the tiny size of our market and next to no incentives making local launches for its ID.4 SUV and ID.3 hatch a low-priority in the global scheme of things. Nevertheless, Volkswagen has promised when the ID.4 does launch it will be a blockbuster, with prices claimed to start around the mid-$50,000 mark for the mid-size electric SUV. The ID.4 offers a relatively long range, starting from 330km on the base car, and has achieved mainstream sales success in Europe.

Toyota bZ4X

Timing: 2023 (est.)

Toyota's first mainstream fully electric offering will be the oddly-named bZ4X, and while the brand recently warned us that it may be more expensive than some expect when it arrives some time in the near future, it will herald a new era for Australia's best-selling car brand, introducing a new e-TNGA architecture. As a proper mid-size SUV, will it be able to replicate the runaway success of the RAV4 in recent years? Time will tell.

Mustang Mach-E

Timing: 2023 (est.)

Ford hasn't confirmed the Mach-E electric SUV will even come to Australia, but with the brand's push to go full electric with hero models like this Mustang-badged SUVand the Ford F150 Lightning, we'd say an Australian launch is all but an inevitability, especially since the Blue Oval intends on selling five PHEV or EVs in its range by the end of 2024. Ford simply sold out of Mach-E's recently, citing very strong sales in Europe, so despite an elongated waitthe Mach-E could add significant numbers when it eventually does arrive Down Under.

Electric Cars Are Coming. How Long Until They Rule the Road?

Around the world, governments and automakers are focused on selling newer, cleaner electric vehicles as a key solution to climate change. Yet it could take years, if not decades, before the technology has a drastic effect on greenhouse gas emissions.

One reason for that? It will take a long time for all the existing gasoline-powered vehicles on the road to reach the end of their life spans.

This fleet turnover can be slow, analysts said, because conventional gasoline-powered cars and trucks are becoming more reliable, breaking down less often and lasting longer on the road. The average light-duty vehicle operating in the United States today is 12 years old, according to IHS Markit, an economic forecasting firm. Thats up from 9.6 years old in 2002.

Engineering quality has gotten significantly better over time, in part because of competition from foreign automakers like Toyota, said Todd Campau, who specializes in automotive aftermarket analysis at IHS Markit.

Age of cars and light trucks on U.S. roads

Newer passenger vehicles still mostly run on gasoline.

And theyre likely to stick around for a while.

Age of cars and light trucks on U.S. roads

Newer passenger vehicles still mostly run on gasoline. And theyre likely to stick around for a while.

Age of cars and light trucks on U.S. roads

Newer passenger vehicles still mostly run on gasoline. And theyre likely to stick around for a while.

Source: 2017 National Household Travel Survey

Today, Americans still buy roughly 17 million gasoline-burning vehicles each year. Each of those cars and light trucks can be expected to stick around for 10 or 20 years as they are sold and resold in used car markets. And even after that, the United States exports hundreds of thousands of older used cars annually to countries such as Mexico or Iraq, where the vehicles can last even longer with repeated repairs.

Cutting emissions from transportation, which accounts for nearly one-third of Americas greenhouse gas emissions, will be a difficult, painstaking task. President Biden has set a goal of bringing the nations emissions down to net zero by 2050. Doing so would likely require replacing virtually all gasoline-powered cars and trucks with cleaner electric vehicles charged largely by low-carbon power sources such as solar, wind or nuclear plants.

If automakers managed to stop selling new gasoline-powered vehicles altogether by around 2035, to account for the lag in turnover, that target might be attainable. Both California and General Motors have announced that they aim to sell only zero-emissions new cars and trucks by that date. But those goals have not yet been universally adopted.

How Fleet Turnover Lags New Car Sales

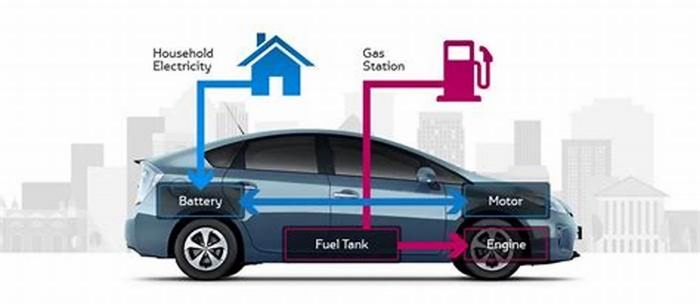

If electric vehicle sales gradually ramped up to 60 percent over the next 30 years, as projected by analysts at IHS Markit, about 40 percent of cars on the road would be electric in 2050.

In order for almost all cars on the road to be electric by 2050, new plug-in sales would need to quickly ramp up to 100 percent in the next 15 years.

How Fleet Turnover Lags New Car Sales

If electric vehicle sales gradually ramped up to 60 percent over the next 30 years, as projected by analysts at IHS Markit, about 40 percent of cars on the road would be electric in 2050.

In order for almost all cars on the road to be electric by 2050, new plug-in sales would need to quickly ramp up to 100 percent in the next 15 years.

How Fleet Turnover Lags New Car Sales

If electric vehicle sales gradually ramped up to 60 percent over the next 30 years, as projected by analysts at IHS Markit, about 40 percent of cars on the road would be electric in 2050.

In order for almost all cars on the road to be electric by 2050, new plug-in sales would need to quickly ramp up to 100 percent in the next 15 years.

How Fleet Turnover Lags New Car Sales

If electric vehicle sales gradually ramped up to 60 percent over the next 30 years, as projected by analysts at IHS Markit, about 40 percent of cars on the road would be electric in 2050.

In order for almost all cars on the road to be electric by 2050, new plug-in sales would need to quickly ramp up to 100 percent in the next 15 years.

How Fleet Turnover Lags New Car Sales

If electric vehicle sales gradually ramped up to 60 percent over the next 30 years, as projected by analysts at I.H.S. Markit, about 40 percent of cars on the road would be electric in 2050.

In order for almost all cars on the road to be electric by 2050, new plug-in sales would need to quickly ramp up to 100 percent in the next 15 years.

Whats more, some economic research suggests, if automakers like G.M. phased out sales of new internal combustion engines, its possible that older gasoline-powered cars might persist for even longer on the roads, as consumers who are unable to afford newer, pricier electric cars instead turn to cheaper used models and drive them more.

So policymakers may need to consider additional strategies to clean up transportation, experts said. That could include policies to buy back and scrap older, less efficient cars already in use. It could also include strategies to reduce Americans dependence on car travel, such as expanding public transit or encouraging biking and walking, so that existing vehicles are driven less often.

Theres an enormous amount of inertia in the system to overcome, said Abdullah Alarfaj, a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University who led a recent study that examined how slow vehicle turnover could be a barrier to quickly cutting emissions from passenger vehicles.

That study suggested several options for speeding up the rate of turnover. For instance, policymakers could focus on electrifying ride-sharing programs like Uber and Lyft first, since those vehicles tend to drive more miles on average and get retired sooner.

There are also options for getting older gas-guzzlers off the road. In 2009, the United States government ran a program called Cash for Clunkers that offered Americans rebates to turn in their older cars for newer, more fuel-efficient models. In all, the government spent about $2.9 billion to help 700,000 car owners upgrade their vehicles.

Some Democrats have proposed reviving that program to accelerate the shift to electric vehicles. Senator Chuck Schumer, the majority leader, has proposed a $392 billion trade-in program that would give consumers vouchers to exchange their traditional gasoline-powered vehicles for zero-emissions vehicles, like electric cars.

Still, a Cash for Clunkers program could prove relatively inefficient, said Christopher R. Knittel, an economist at the M.I.T. Sloan School of Management who has studied the policy. The original program often benefited Americans who were on the verge of trading in their vehicles anyway, he said, and it often missed the drivers who were driving particularly gas-guzzling vehicles long distances.

Its a blunt tool, although there are likely ways to improve the program, Dr. Knittel said.

As an alternative, Dr. Knittel noted, a tax on carbon dioxide emissions could prove more effective, by increasing the price of gasoline and giving drivers a clear incentive both to upgrade to cleaner vehicles and drive less. Yet lawmakers have often steered clear of hiking gas taxes, worried about both political blowback and the effects on low-income drivers.

That leaves a final, potentially powerful option: Cities could reshape their housing and transportation systems so that Americans are less reliant on automobiles to get around. Some cities have had success in reducing their dependency on cars: Since 1990, Paris has reduced the share of trips taken by car in city limits by 45 percent, by building new bus and train lines, expanding bike paths and sidewalks, and restricting vehicle traffic on certain streets. In Germany, the city of Heidelberg has made reducing car dependency the central plank of its plan to reduce emissions.

Most American cities are far from looking like Paris or Heidelberg. But there are still plenty of changes that cities could make to reduce car travel at the margins, said Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America, a transit advocacy group. That could entail adding denser housing in walkable urban areas, expanding public transportation or making neighborhoods safer to walk around. Governments could also redirect spending away from constructing new roads that tend to induce sprawl and more driving.

While were ramping up to full electrification, we want to make sure that were not increasing emissions from all the other cars still on the road, said Ms. Osborne.

Finding ways to curb private vehicle travel even modestly could have a significant impact, researchers have found.

One recent study in Nature Climate Change looked at what it would take to drastically slash emissions from passenger vehicles in the United States. If Americans keep driving more total miles each year, as they have historically done, the country may need some 350 million electric vehicles by 2050 a daunting figure. Doing so would also require a massive expansion of the nations electric grid and vast new supplies of battery materials like lithium and cobalt.

But the study also explored what would happen if the United States kept overall vehicle travel flat for the next 30 years. In that scenario, the researchers found, the United States could cut emissions just as deeply with around 205 million electric vehicles.

Were not saying everyone would have to take the bus to work, said Alexandre Milovanoff, an energy and sustainability researcher at the University of Toronto and lead author of the study. A lot of people do need private vehicles to get around, and in those cases, electric cars make a lot of sense as a climate solution. But we shouldnt limit ourselves to thinking about electric vehicles as the only option here.

To be sure, its conceivable that fleet turnover could end up happening even faster than current models predict as automakers invest more heavily in electrification. One possibility is that the nation reaches a tipping point: As more and more plug-in vehicles start appearing on the roads, gas stations and crude oil refineries start closing down, while auto repair shops shift to mainly servicing electric models. Eventually, it might be too much of a hassle for people to own conventional gasoline-powered cars.

It would not shock me if the transition eventually starts accelerating, said Dr. Knittel of M.I.T. Right now it can be inconvenient to own an electric vehicle if there are no charging stations around. But if we do get to a world where there are charging stations everywhere and few gas stations around, suddenly its less convenient to own a conventional vehicle.