Will hydrogen overtake EV

Hydrogen cars wont overtake electric vehicles because theyre hampered by the laws ofscience

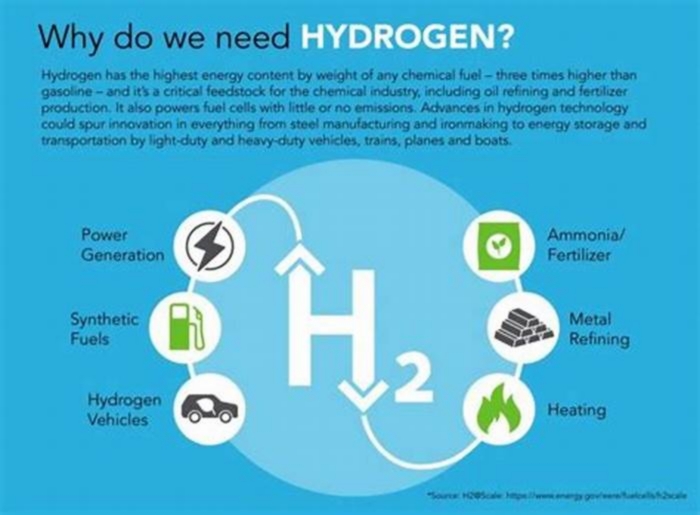

Hydrogen has long been touted as the future for passenger cars. The hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV), which simply runs on pressurised hydrogen from a fuelling station, produces zero carbon emissions from its exhaust. It can be filled as quickly as a fossil-fuel equivalent and offers a similar driving distance to petrol. It has some heavyweight backing, with Toyota for instance launching the second-generation Mirai later in 2020.

The Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association recently produced a report extolling hydrogen vehicles. Among other points, it said that the carbon footprint is an order of magnitude better than electric vehicles: 2.7g of carbon dioxide per kilometre compared to 20.9g.

All the same, I think hydrogen fuel cells are a flawed concept. I do think hydrogen will play a significant role in achieving net zero carbon emissions by replacing natural gas in industrial and domestic heating. But I struggle to see how hydrogen can compete with electric vehicles, and this view has been reinforced by two recent pronouncements

A report by BloombergNEF concluded:

The bulk of the car, bus and light-truck market looks set to adopt [battery electric technology], which are a cheaper solution than fuel cells.

Volkswagen, meanwhile, made a statement comparing the energy efficiency of the technologies. The conclusion is clear said the company. In the case of the passenger car, everything speaks in favour of the battery and practically nothing speaks in favour of hydrogen.

Hydrogens efficiency problem

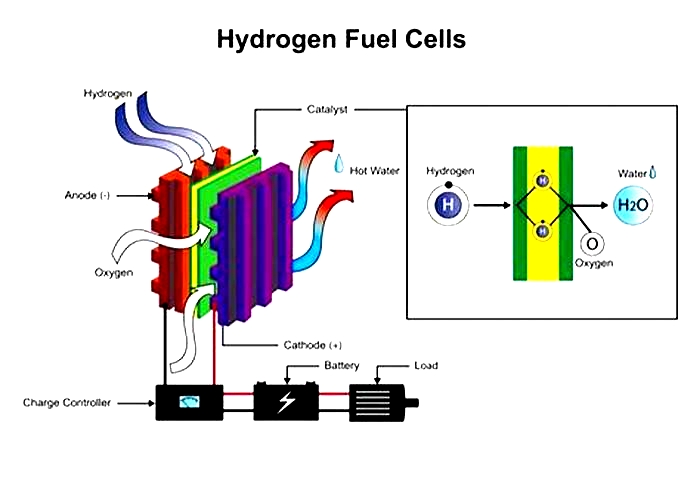

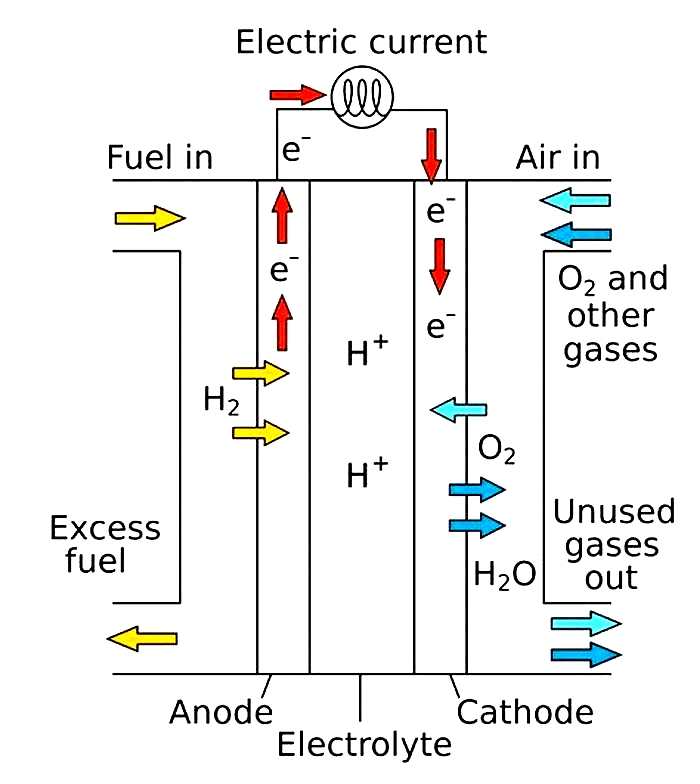

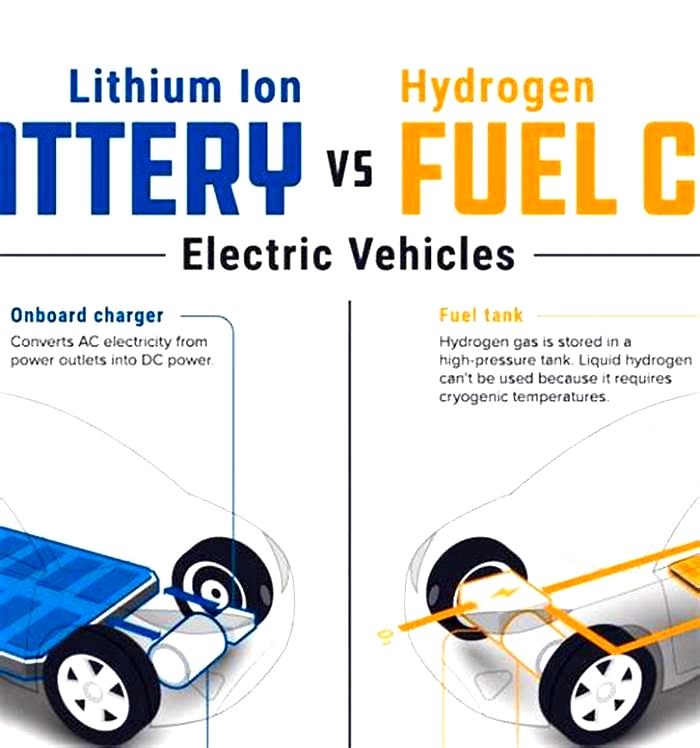

The reason why hydrogen is inefficient is because the energy must move from wire to gas to wire in order to power a car. This is sometimes called the energy vector transition.

Lets take 100 watts of electricity produced by a renewable source such as a wind turbine. To power an FCEV, that energy has to be converted into hydrogen, possibly by passing it through water (the electrolysis process). This is around 75% energy-efficient, so around one-quarter of the electricity is automatically lost.

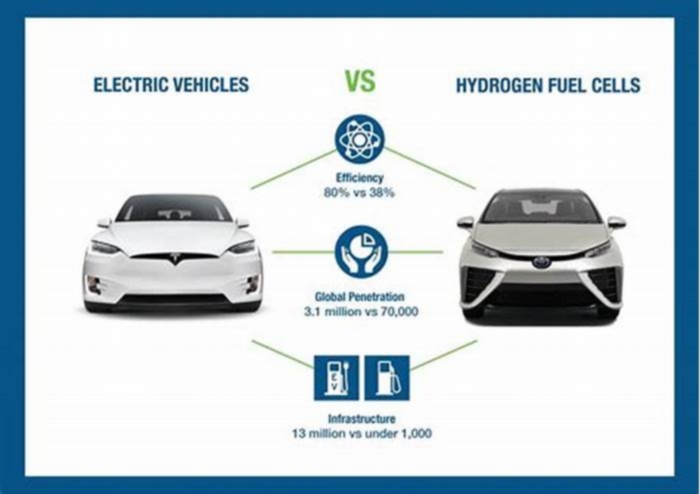

The hydrogen produced has to be compressed, chilled and transported to the hydrogen station, a process that is around 90% efficient. Once inside the vehicle, the hydrogen needs to be converted into electricity, which is 60% efficient. Finally the electricity used in the motor to move the vehicle is is around 95% efficient. Put together, only 38% of the original electricity 38 watts out of 100 are used.

With electric vehicles, the energy runs on wires all the way from the source to the car. The same 100 watts of power from the same turbine loses about 5% of efficiency in this journey through the grid (in the case of hydrogen, Im assuming the conversion takes place onsite at the wind farm).

You lose a further 10% of energy from charging and discharging the lithium-ion battery, plus another 5% from using the electricity to make the vehicle move. So you are down to 80 watts as shown in the figure opposite.

In other words, the hydrogen fuel cell requires double the amount of energy. To quote BMW: The overall efficiency in the power-to-vehicle-drive energy chain is therefore only half the level of [an electric vehicle].

Swap shops

There are around 5 million electric vehicles on the roads, and sales have been rising strongly. This is at best only around 0.5% of the global total, though still in a different league to hydrogen, which had achieved around 7,500 car sales worldwide by the end of 2019.

Hydrogen still has very few refuelling stations and building them is hardly going to be a priority during the coronavirus pandemic, yet enthusiasts for the longer term point to several benefits over electric vehicles: drivers can refuel much more quickly and drive much further per tank. Like me, many people remain reluctant to buy an electric car for these reasons.

China, with electric vehicle sales of more than one million a year, is demonstrating how these issues can be addressed. The infrastructure is being built for owners to be able to drive into forecourts and swap batteries quickly. NIO, the Shanghai-based car manufacturer, claims a three-minute swap time at these stations.

China is planning to build a large number of them. BJEV, the electric-car subsidiary of motor manufacturer BAIC, is investing 1.3 billion (1.2 billion) to build 3,000 battery charging stations across the country in the next couple of years.

Not only is this an answer to the range anxiety of prospective electric car owners, it also addresses their high cost. Batteries make up about 25% of the average sale price of electric vehicles, which is still some way higher than petrol or diesel equivalents.

By using the swap concept, the battery could be rented, with part of the swap cost being a fee for rental. That would reduce the purchase cost and incentivise public uptake. The swap batteries could also be charged using surplus renewable electricity a huge environmental positive.

Admittedly, this concept would require a degree of standardisation in battery technology that may not be to the liking of European car manufacturers. The fact that battery technology could soon make it possible to power cars for a million miles might make the business model more attractive.

It may not be workable with heavier vehicles such as vans or trucks, since they need very big batteries. Here, hydrogen may indeed come out on top as BloombergNEF predicted in its recent report.

Finally a word on the claims on carbon emissions from that Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association report I mentioned earlier. I checked the source of the statistics, which revealed they were comparing hydrogen made from purely renwewable electricity with electric vehicles powered by electricity from fossil fuels.

If both were charged using renewable electricity, the carbon footprint would be similar. The original report was funded by industry consortium H2 Mobility, so its a good example of the need to be careful with information in this area.

Will hydrogen overtake batteries in the race for zero-emission cars?

Hydrogen is a beguiling substance: the lightest element. When it reacts with oxygen it produces only water and releases abundant energy. The invisible gas looks like a clean fuel of the future. Some of the worlds top automotive executives are hoping it will dethrone the battery as the technology of choice for zero-emissions driving.

Our EV mythbusters series has looked at concerns ranging from car fires to battery mining, range anxiety to cost concerns and carbon footprints. Many critics of electric vehicles argue that we should not ditch petrol and diesel engines. This article asks: could hydrogen offer a third way and overtake the battery?

The claim

Many of the strongest claims for hydrogens role in the automotive world come from chief executives at the heart of the industry. Japans Toyota is the most vocal proponent of hydrogen, and its chair, Akio Toyoda, last month said he believed the share of battery cars would peak at 30%, with hydrogen and internal combustion engines making up the rest. Toyotas Mirai is one of the only hydrogen-powered cars that is widely available, alongside the Nexo SUV from South Koreas Hyundai.

Oliver Zipse, the boss of the German manufacturer BMW, said last year: Hydrogen is the missing piece in the jigsaw when it comes to emission-free mobility. BMW may be investing heavily in battery technology but the company has its BMW iX5 Hydrogen fuel cell car in testing albeit using Toyota fuel cells. Zipse said: One technology on its own will not be enough to enable climate-neutral mobility worldwide.

The science

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe but that does not mean it is easy to come by on Earth. Most pure hydrogen today is made by splitting carbon from methane, but that produces carbon emissions. Zero-emissions green hydrogen comes from electrolysis: using clean electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

To use hydrogen as a fuel it can be burned, or it can be used in a fuel cell: the hydrogen reacts with the oxygen from the air in the presence of a catalyst (often made from expensive platinum). That strips electrons that can run through an electric circuit, charging a battery that can power an electric motor.

Hydrogen offers refuelling in four minutes, higher payloads and longer range, according to Jean-Michel Billig, the chief technology officer for hydrogen fuel cell vehicle development at Stellantis. (The Mirai goes 400 miles on a fill-up.) Stellantis, which last month started production of hydrogen vans in France and Poland, is targeting businesses that want vehicles in constant use and do not want the downtime required for charging.

They need to be on the roads, Billig said. A taxi not running is losing money.

Many energy experts do not share the enthusiasm of the hydrogen carmakers

Stellantis thinks it can drive the sticker price down. Billig said that he expected by the end of this decade, hydrogen mobility or BEV will be equivalent from a cost perspective although the company will make both.

Many energy experts do not share the enthusiasm of the hydrogen carmakers. The Tesla boss Elon Musk describes the tech as fool sells: why use green electricity to make hydrogen when you can use that same electricity to power the car?

Every transformation of energy involves wasted heat. That means that hydrogen fuels inevitably deliver less energy to the vehicle. (Those losses increase much further if the hydrogen is burned directly or used to make e-fuels that can replace petrol or diesel in a noisy, hot internal combustion engine.)

David Cebon, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Cambridge, said: If you use green hydrogen it takes about three times more electricity to make the hydrogen to power a car than it does just to charge a battery.

That could improve slightly but not enough to challenge batteries. Its difficult to do very much better, Cebon said.

Michael Liebreich, the chair of Liebreich Associates and the founder of the analyst firm Bloomberg New Energy Finance, created an influential hydrogen ladder a league table ranking hydrogen uses on whether there are cheaper, easier or more likely options. He placed hydrogen for cars in the row of doom, with very little chance of even a niche market.

Can hydrogen overtake batteries in cars? The answer is no, said Liebreich, without a moments hesitation. Carmakers betting on a large share for hydrogen are just wrong, and heading for an expensive disappointment, he added.

The key problem for hydrogen cars is not the fuel cell but actually getting the clean hydrogen where it is needed. The gas is highly flammable with all the safety concerns that entails must be stored under pressure and leaks easily. It also carries less energy per unit volume than fossil fuels, meaning it would require many times more tankers unless on-site electrolysers are used.

Investments are coming in hydrogen supplies, with heavy government subsidies in the US and Europe. But so far there has been a chicken-and-egg problem: buyers dont want hydrogen cars because they cant fill them, and there are no filling stations because there are no cars. Across Europe there are 178 hydrogen filling stations, half of which are in Germany, according to the European Hydrogen Observatory. Compare nine UK hydrogen stations with 8,300 petrol stations or 31,000 public charging locations (not counting plugs at homes).

Any caveats?

So why does the International Energy Agency think that hydrogen will account for 16% of road transport in 2050 in its pathway to net zero? The answer lies mostly with bigger vehicles such as buses and lorries.

Liebreich said he was convinced that batteries would still dominate energy supply for heavy goods vehicles to the point of co-founding a lorry charging company. There might be some hydrogen in HGVs but it will be the minority, he said.

Even Toyota acknowledges that hydrogen in cars has so far not been successful, mainly because of the lack of fuel supply, according to its technical chief, Hiroki Nakajima, speaking to Autocar in October. Lorries and long-distance buses offer a better hope for the technology, although it is also prototyping a hydrogen version of its Hilux pickup truck.

The verdict

The economics of hydrogen will change as governments enthusiasms wax or wane. Other things could change: technology could improve (within limits) and make the gas more attractive, and prospectors may be able to find cheaper white hydrogen drilled from the ground.

Yet for cars the die appears to be cast: batteries are already the post-petrol choice for almost every manufacturer. In the UK there have been fewer than 300 sales of hydrogen vehicles over 20 years, compared with 1m electric cars, according to the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders.

Batteries domination is likely to be extended as the money pouring into research and infrastructure addresses questions of range and charging times. Compared with that flood of investment, hydrogen is a trickle.

Hydrogens advocates now face the question of whether they can build profitable businesses in longer-distance, heavy-duty road transport. They need an answer soon on where they will source enough green, cheap hydrogen and whether the gas would be better used elsewhere.